An old man remembers the time when soldiers rode into his Texas town and he heard that they were no longer slaves, they were free. What was it like to experience such a profound historical moment? Hear him tell the story in a US Library of Congress collection of interviews with people who recounted that day: Voices Remembering Slavery: Freed People Tell Their Stories. They are openly available along with records from contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter. From the past to the present, archives have a lot to offer the online researcher!

Let’s explore the options in this month’s focus on Archival Methods for the Online Researcher. In this issue of When the Field is Online you’ll find an overview of issues associated with archival research, interviews with two archivists, links to open-access archives, and resources so you can learn more. Looking ahead to November, we will observe Academic Writing Month (AcWriMo) with a focus on originality. In addition to the free monthly newsletter, paid subscribers will gain access to live chats, guest posts, and additional features. I hope you’ll join me!

What is archival research, and why is it useful for social researchers?

Social researchers might think that archival methods are the domain of the humanities but in today's world we leap past such boundaries. Researchers benefit from using primary sources regardless of discipline. Documents and other original source materials may be consulted and analyzed to ask new questions of old data, provide a comparison over time or between geographic areas, verify or challenge existing findings, or draw together evidence from disparate sources to provide a bigger picture. Analysis of archival data might be central to the study, or primary source materials can help us offer a more nuanced description of personal, social, or cultural contexts of the research problem.

Lewis-Beck et al (2004) defined archival research in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods:

For the social scientist, archival research can be defined as the locating, evaluating, and systematic interpretation and analysis of sources found in archives. Archives contain official sources (such as government papers), organizational records, medical records, personal collections, and other contextual materials. Primary research data are also found, such as those created by the investigator during the research process, and include transcripts or tapes of interviews, field notes, personal diaries, observations, unpublished manuscripts, and associated correspondence. Archives also comprise the cultural and material residues of both institutional and theoretical or intellectual processes, for example, in the development of ideas within a key social science department.

Many of those sources come in the form of documents. In a Sage Research Methods Foundations essay, Lindsay Prior (2019) defined documents as:

Document is a word derived from the Latin verb for teaching: docere. A document in that sense is something that functions to explain, instruct, warn, exemplify, substantiate, or prove. [T]he word document tends to be used as a noun—to denote a physical or electronic container of some kind, and what is contained is typically text and related forms of inscription.

Thus, letters, diaries, laboratory notebooks, clinical notes, kitchen recipes, transcribed speeches and interviews, reports, notices on posts and doors, graffiti on walls, musical scores, text messages, and train tickets all qualify as documents along with a myriad of other forms.

In an age in which communication using images (via, e.g., social media, selfies, and emoticons) can take precedence over communication using text, the notion of what a document “is” has, necessarily, to be broad. Essentially, however, what marks an object as a document is not what it contains nor its physical or electronic format, but its role and use as a conveyor of information.

I agree with Prior because in our multimedia world we can’t be limited by thinking of the term documents as solely a descriptor for written materials! Archives contain every type of written work as well as music, films, photographs, artwork and commercial art.

Technology, documents, and archival research

Archival research has changed dramatically now that so much material is available in searchable databases offered online.

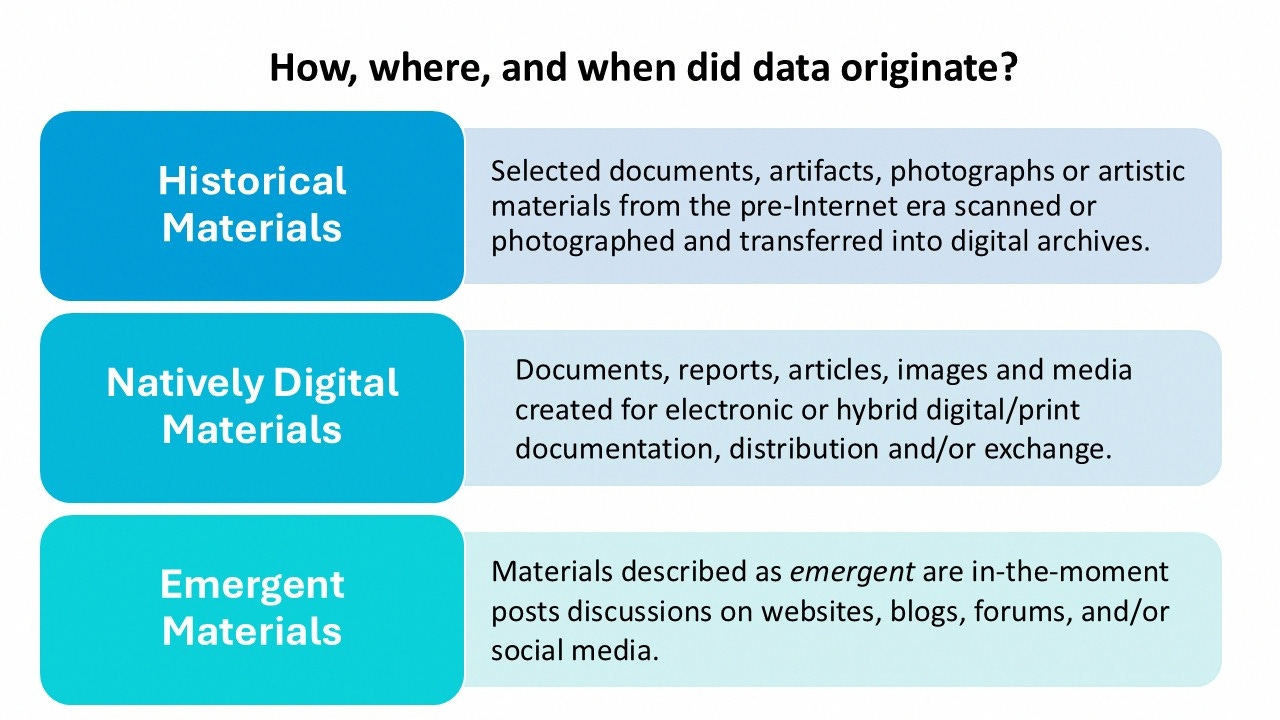

While we might think of archives as repositories of historical materials, we can also find contemporary resources. I classify documents by the time frame when they were created:

Historical materials, created before the digital era, must be scanned or photographed in order to be accessed in an online archive. Materials can include news or magazine articles, letters, diaries, oral histories, maps, census or government records, photographs, speech, radio or film clips. Extensive collections of historical materials can be accessed from libraries, museums, national or foundation archives, historical societies, and other sites. Some collections require permission to access and use, others are open to anyone. Even though digitization is making progress, some materials from the pre-Internet era are not available electronically. Depending on the archive, scanning of particular documents can be requested but others still need to be reviewed by hand. Historical materials can also be privately held: families have pictures, writings, and other treasures from past generations.

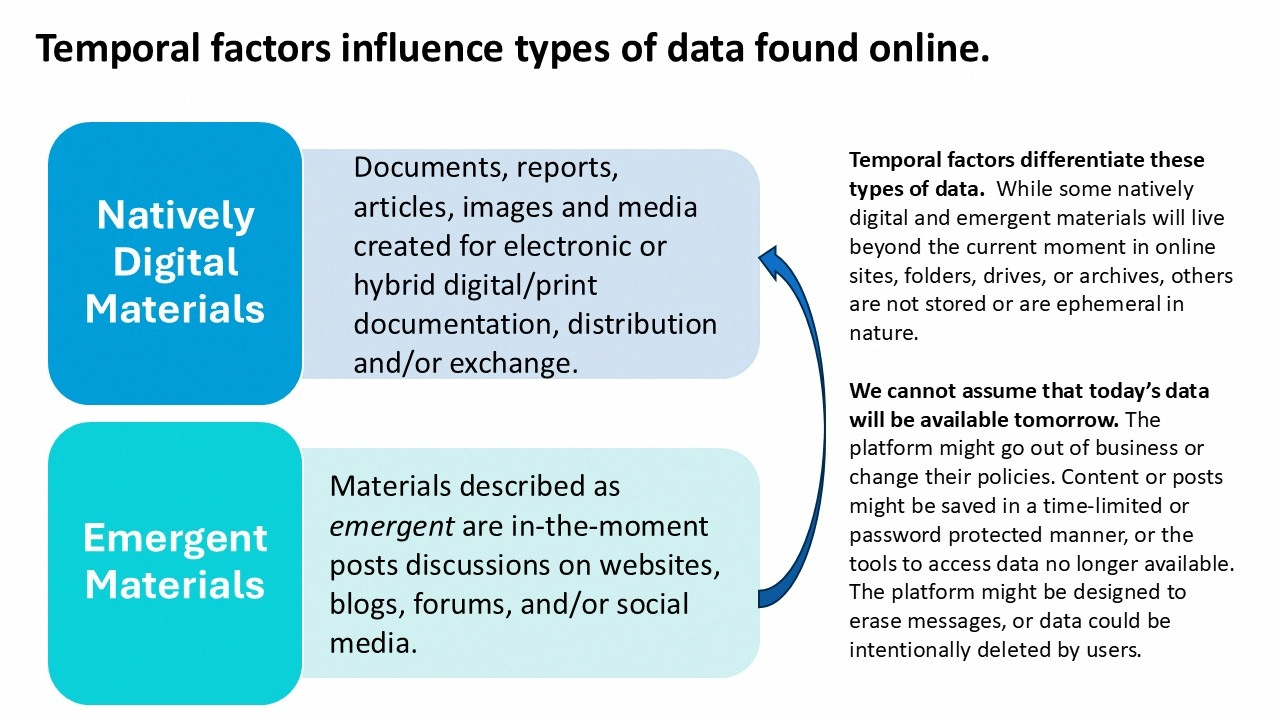

Natively digital materials were created in and for the digital age. Materials created in the late 20th and 21st century are likely to have an electronic version, even if they were also released in print. For example, a business researcher can find annual reports that were distributed as print brochures but also posted on a website. These documents typically have internal or external links to related media or other sources or are interactive.

Emergent materials are being created every minute of the day when Internet users log on and post. Emergent materials are characterized by their immediacy; they might be temporary, seen in the moment then replaced by new posts. Emergent materials include posted comments and media, questions and responses in online discussion forums, groups, games, communities, blogs and/or social media. Private types of emergent materials could include emails and 1-to-1 messaging.

It might seem that everything from everywhere is available to us online but that is not the case. Natively digital materials may or may not be organized and saved in archives. Commercial platforms go out of business or change policies in regard to who can access and use them. Natively emergent materials often ephemeral. While natively digital, they may or may not be saved.

Maybe we need to think about our own work differently and be mindful of how and where it is saved. We might need to create our own archives… but that is an idea we’ll explore in another post!

Archival research then and now

Many years ago, when I was conducting an action research case study for my Masters thesis, I stumbled across historical antecedents to my project. One thing led to another, and I wound up doing extensive archival research in the Cornell University Library and the Rockefeller Archive Center (RAC). Critically relevant material was in the form of personal correspondence, so I could not have found this information in published literature. Letters offer a unique form of data, representing thoughts, feelings, and observations of the writer. Some are formal or professional, and others are deeply personal. If we are fortunate enough to have access to the response, we can observe an unfolding conversation that may occur over a period of time-- sometimes across a span of years. I was fortunate to have this kind of opportunity.

By archival research I mean digging through boxes, taking letters out of envelopes, and reading original handwritten notes. I was particularly intrigued by correspondence between the person I was studying, Alexander Drummond, and his program officer at the Rockefeller Foundation, David Stevens. Unlike today’s time-limited grantmaking, Rockefeller supported Drummond’s work throughout his career. Over years of letter-writing they had a lot to say about cultural democracy and ways to give voice to diverse stories – the same kinds of issues that interested me! I was intrigued. After reading Drummond’s cache of letters from Stevens, I went to the Rockefeller Archive Center to read the other side of exchange. (As an aside, I can’t help but mention that these kinds of discoveries happen when you do your own reading and come across important new directions I didn’t “prompt” or could not have predicted!)

This meaningful research experience has stayed with me. I was motivated to explore whether and how the research I did the old-fashioned way would be different now. I interviewed Elaine Engst, the Director of the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections and University Archivist, Emerita, a couple of years ago, when I was managing Sage Methodspace. Last week I interviewed Heather Oswald, Assistant Director for Access at the Rockefeller Archive Center last week. Listen to find out more about what sources get digitized and why, as well as tips about how to access and use archives in your own research.

and

Follow these links to learn more about the sites and examples we discussed:

Cornell University: While the Cornell library is accessible to members of the university community and alumni, Rare and Manuscript Collections are open access. See the Archival Guides, and Instructions for finding materials. Check out Online Exhibitions: Interpretative and related materials from Visions of Dante to HipHop.

Catalog entries we discussed in the interview:

Alexander Drummond: limited catalog entry

Ezra Cornell: detailed catalog entry

Finding Aids:

Alexander Drummond: topic list, no access to digital versions

Ezra Cornell: descriptive list, access to digital versions

Primary Sources: Physical or Digital?

In short, here is the answer to my overarching question about what is archival research like now? It is the same, and different. Not all historical materials are digitized so while we might find that the material exists and is housed an archive, that doesn’t necessarily mean it is available online. Or it might could be digitized but in a private archive where permission is needed for access. We might *gasp* have to actually go there in person and read the paper documents.

If I were studying the same collection, I would still need to go to Cornell or the RAC and pore through boxes. However, I could use an online catalog and finding aid to focus my search. On the other hand, if I were studying a different figure, one whose work attracted the funding necessary to digitize the collection, I might be able to access, download, and read the source materials online. Clearly, time and money are the deciding factor, and not every topic that interests you also motivates the individuals or funding agencies who support such efforts.

That said, I can easily get lost wandering the fabulous array of digital archives! Take a look at some of these examples, and maybe you will find some sources to explore.

Visit Archives

Get lost in the virtual stacks when you click into these open-access archives!

Government archives contain public records, census and other reports.

Archives Nationales (France)

CAARA - Council of Australasian Archives and Records Authorities

National Archives and Records Administration (US) (See Online Research Tools and Aids .)

National Archives (UK)

Museum and cultural center archives contain examples from their collections, records of exhibitions, and related materials.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (and free publications)

National Libraries contain links to archived publications, media, and historical materials.

Library of Congress (US)

British Library (UK)

and Endangered Archives Programme (with preservation grants)Library of Congress (US)

Open Access Collections of Letters:

British Library: Letters

Digital Public Library of America: Letters

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letters

Rockefeller Archive Center Online Collections

US Library of Congress: Letters

US National Archives: Letters

There are too many to list! Have a favorite archive? Share it in the comments area.

On-site Physical Archives

Find materials you’ll need to see first-hand? If you plan to visit an physical archive site, use Kristan Lucas’s practical advice from The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods:

Identify a Clear Goal: Archival researchers should begin with a clear research question and a basic idea of what kinds of archival data can be helpful to answering their question. At a minimum, researchers should have a clear topic and time period in mind that will help them target their search efforts. Ideally, the project’s scope should be narrow enough to allow the researcher to explore the full depth of the archival materials.

Make an Initial Inquiry: As a next step, researchers should identify an archive that contains relevant materials or collections. Conducting an Internet search or asking subject matter experts can generate promising direction. Once an archive is identified, researchers should contact the archive directly to make an initial inquiry. As part of the inquiry, researchers should explain their project, indicate the materials they will want to access, and request permission to access materials. Researchers may also ask questions about other relevant materials that may be available, the amount of material in the collection (is it 1 box or 50?), whether any portion of the collection has been digitized, and available technology for recording purposes (e.g., scanners, photocopiers, no technology). The more information researchers are able to gather during the initial inquiry, the better they will be able to plan their visit to the archive.

Participate in an Orientation Interview: Upon arrival at the archive, researchers should participate in an orientation interview with the archivist. The purpose of the orientation interview is for the researcher and archivist to engage in a conversation about the proposed project and its aims. Based on this conversation, the archivist will provide researchers with information about relevant holdings, including related collections that might not be cross-referenced, collections that have yet to be processed, or even collections at other archives.

Learn and Follow the Rules: Archives have developed strict rules to protect the longevity of the materials. Therefore, it is essential that researchers honor all rules. Taking shortcuts or bending rules can seriously limit, and possibly terminate, researchers’ access to archival materials. Each archive will have its own set of rules. However, common rules include forbidding any food or beverages in the archives, forbidding the use of pens, limiting use of phones and cameras, making researchers stow book bags and jackets in a coat room, requiring researchers to wear gloves when touching materials, having a specific way to open folders and turn pages, and only permitting selected materials to be copied.

More about Archival Methods

How-to Resources

The Society of American Archivists, a professional association dedicated to the needs and interests of archives and archivists, has put together an open-access resource that can help you get started. See Using Archives A Guide to Effective Research by Laura Schmidt.

Worksheets to use when analyzing photos, written documents, artifacts, posters, maps, cartoons, videos, and sound recording.

Gordon, D. (2018, November 20). Reading the Archives as Sources. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Retrieved 10 Oct. 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-227.

Case Studies in Archival Ethics from the Society of American Archivists

Documentary Research in the Social Sciences by Dr. Malcolm Tight

Doing Document Analysis: A Practice-Oriented Method by Kristin Asdal and Hilde Reinertsen

Doing Conversation, Discourse and Document Analysis by Tim Rapley

Open Access Articles

Eyal, H., Aharoni, S. B., & Preser, R. (2024). The Archival Phase in Feminist Organizations: Methodological Suggestions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241254005

Abstract. The article is based on a series of interviews (61) and a multi-sited ethnography conducted during 2019–2021 which traced archival records of 20 feminist organizations in Israel: local women’s peace organizations (FPAs) and Rape Crisis Centres (RCCs). We describe the study and the complex methodological concerns and meta-questions relating to the study of feminist community archives in relation to content (types of testimonials or records), method of organization (archival practices like cataloging or digitization) and activists’ perspectives concerning future preservation and access. In order to overcome these challenges, we suggest six methodological principles which may apply to the study of civil society organizations that were established between the 1970s–1990s: the importance of identifying researchers’ positionality vis a-vis the archive; the politics of knowledge and intersectional identities; avoiding judgment of informal archival practices; identifying who sets the rules; silence and self-silencing; and recognition of invisible labor.

Hegarty, K. (2023). Imagining permanence on the web: Tracing the meanings of long-term preservation among the subjects of web archives. New Media & Society, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231187031

Abstract. This article explores how web archiving impacts the online communication practices of individuals whose personal websites have been archived by major public libraries. Drawing on interviews with website creators and analysis of their written reflections on the archiving process, it demonstrates how web archiving alters the meanings people attach to their online activity. In most cases, the preservation of their website in a national web archive sees individuals perceive their communication practices as having wider cultural and historical significance. These meanings are shaped by the distinctive interaction between archiving and archived actors and propelled by imaginaries surrounding the culture and history of the collecting institution. Based on these findings, this article argues that web archiving can be productively understood as an intervention in the dynamics of online sociality and calls for reflexive archival and research practices that attend to the short- and long-term impacts of altering the visibility of online material.

Hodder, J., & Beckingham, D. (2022). Digital archives and recombinant historical geographies. Progress in Human Geography, 46(6), 1298-1310. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221103603

Abstract. This article considers how digitisation is reshaping archival research in geography. Digitisation is more than a technical convenience, something that simply speeds up existing ways of working. Through novel practices of recombination, digital archive platforms enable researchers to extract and recombine fragments of historical information, drawn across multiple periods, places, collections and contexts. This represents a fundamental change in how we research the past. In this paper, we conceptualise recombination as an uneven geographical phenomenon, we situate it within the shifting political and economic infrastructures of archives, and pose a series of ethical questions for geographers to consider.

Maleki, N., & Salubi, O. (2023). Framework for the Assessment of Virtual Archival Systems and Provision of Virtual Archival Services for Environmental Sustainability in South Africa. Collections, 19(4), 571-582. https://doi.org/10.1177/15501906231215118

Abstract. Archival records/resources in electronic and those that only existed in physical formats have been made available to a larger audience and received much more usage as a result of digitization and remote accessibility. Virtual archives can help to reduce the environmental impact of traditional archival practices by storing and sharing information digitally rather than physically. The aim of this paper is to assess and develop a framework for the delivery of a virtual archive system tailored to the needs of both users and archival institutions for the promotion of environmental sustainability especially in developing countries. The qualitative research explained user expectations and perspectives on the provision of a newly established electronic archival system for the provision of virtual archive services at an archival institution in the City of Cape Town. This paper anchored on the Expectation Confirmation Theory proposed the Virtual archival systems expectations and satisfaction (VASES) framework to identify electronic archival system users’ expectations, measure perceived performance of electronic archival systems, and assess confirmation and satisfaction.

O'Sullivan, C. (2005). Diaries, On-line Diaries, and the Future Loss to Archives; or, Blogs and the Blogging Bloggers Who Blog Them. The American Archivist, 68(1), 53-73. https://doi.org/10.17723/aarc.68.1.7k7712167p6035vt

Abstract. This paper examines the archival potential of blogs, a popular form of electronic record in which personal accounts and commentaries are entered regularly in an on-line journal. A historical survey of the diary—the blog's paper-based antecedent—suggests how the two records are alike and where they diverge, taking into account their evidential values, their seemingly contradictory public and private qualities, and their very diverse physical natures. The paper discusses the role that traditional archives should play in preserving blogs, while considering the implications that their loss would have for our cultural memory, and offering some suggestions for ensuring their preservation.

Ringel, S., & Ribak, R. (2024). Platformizing the Past: The Social Media Logic of Archival Digitization. Social Media + Society, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051241228596

Abstract. Heritage institutions increasingly incorporate social media logic into their efforts to digitize archival sources. This study is based on an ethnographic exploration of the National Library of Israel’s (NLI) digitization endeavors, with the aim of understanding how the transition from analog to digital materials aligns with the principles of platformization. By conducting observations, examining reports, and interviewing NLI professionals, we shed light on the pervasive influence of social media logic within public sector institutions, such as the National Library. We argue that the digitization process of archival documents is a form of platformization, and its impact is evident even before the content is disseminated, exposed, and uploaded to social media platforms. Furthermore, our analysis underscores how social media logic is a guiding force behind the NLI’s digitization strategy, encompassing the selection of materials and the construction of a digital archive for future generations.

Roulston, K. (2019). Using Archival Data to Examine Interview Methods: The Case of the Former Slave Project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919867003

Abstract. Unlike historians, qualitative researchers’ engagement in studies in which archival sources form the core data corpus is less common than the exploration of newly generated data. Following scholars who have argued for secondary analysis of qualitative data, in this article, I illustrate how qualitative researchers might explore archival data methodologically. Examinations of archival records help us think about how research methods change over time and compare approaches to current practice. This article draws on records from the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), one of the New Deal initiatives launched by President F. D. Roosevelt in the United States. The FWP was a work relief program administered during the Depression years in the 1930s that employed 6,500 white-collar workers as fieldworkers, writers, and editors to solicit stories from 1,000s of men and women across the country, including stories of over 4,000 former slaves. This article focuses on the role of interviewing in the Former Slave Project, examining methodological issues of concern observed by administrators and critics of the project, along with what we might learn and how we might think about these issues in contemporary interview research.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

No AI tools were used for any stage of this writing.

References

Lucas, K. (2017). The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. In M. Allen (Ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, California. Retrieved from https://methods.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-communication-research-methods. doi:10.4135/9781483381411

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Bryman, A., & Futing Liao, T. (2004). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. doi: 10.4135/9781412950589

Cover image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay

Human Intelligence badge by