Welcome to 2025! Let’s keep learning about qualitative research in the digital age!

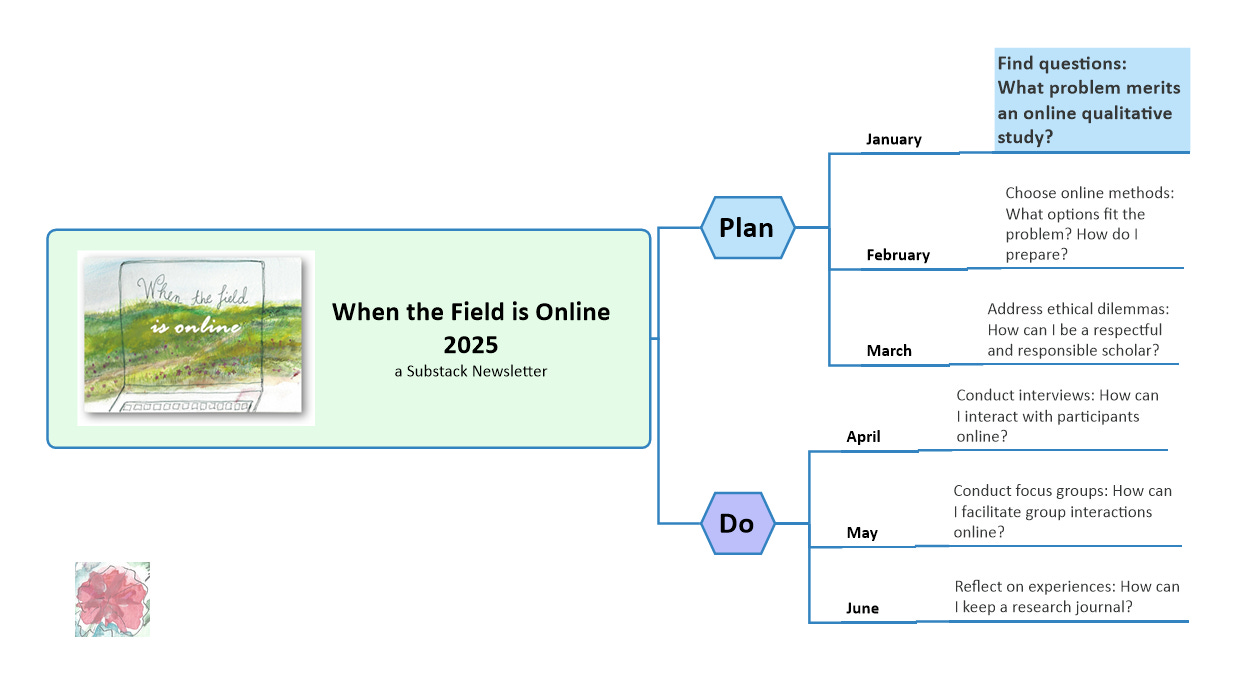

Information and communications technologies (ICTs) can do many things; as a qualitative researchers I’m most interested in the potential for connecting with people, whether participants or collaborative partners, and with secondary or extant sources of data. In the first three months of 2025 we’ll look at questions and decisions associated with designing and planning qualitative studies you intend to conduct online.

In the second three months we will look at ways to carry out your plans to conduct interviews or focus groups online. We’ll wind up this half of the year with a June newsletter about research journals. I welcome your input on topics to include in the second half of the year, so feel free to comment or message me!

In addition to the free newsletter, I will offer interactive chats and office hours for paid subscribers.

What’s the problem?

Whether you decide to conduct a large, complex study or a small project for a course assignment, you must begin by deciding what to study. As a would-be qualitative scholar you must determine the phenomenon, issue, topic, or theory to study, before deciding how to investigate it. For simplicity’s sake we’ll just use the term “problem” to refer to the impetus for the study.

The research problem addresses what researchers perceive is wrong, missing, or puzzling, or what requires changing, in the world. Presentations of the research problem typically set the stage for the study that will be, or that was, conducted by offering evidence that the problem exists and for whom and by establishing the significance of the problem and why it requires formal inquiry. (Given, 2008 p. 734)

When I supervised doctoral students at this initial pre-design stage, I asked them to think through some key questions that help to focus the process. As Booth, Columb, and Williams observe in their classic text, The Craft of Research:

If you are new to research, the freedom to pick your own topic can seem daunting. Where do you begin? How do you tell a good topic from a bad one? (p. 52)

Usually the issue is not so much a “bad” problem, but one that is too general or vaguely defined. Given the additional complexities of an online study, defining a precise problem is an essential first step.

Building on Booth’s suggestions, here are some questions to stimulate or clarify your thinking and help you move from “I wonder…?” to a clearly-defined, research-worthy problem.

Is the problem new or old? Is it a well-studied or an emerging problem?

If it is an emerging problem, is there a similar issue that has been previously studied, or has the problem been studied in other contexts or disciplines?

How does it fit into a larger developmental or social context? How and why has the problem changed over time?

What is the scope of the problem? Is it a problem experienced by individuals, groups, organizations, or the world at large?

Is the problem specific to particular settings, cultures, localities, populations, demographic groups, or is it a wide-spread issue?

Beyond your own interest, do others think this is a problem worth studying?

Are you interested in problems that occur primarily in the real world or online?

Online researchers have additional questions to consider. Answers will inform the next stage of your design process, including choice of methodology, methods, population, and the information and technology tools (ICTs) best suited to the study.

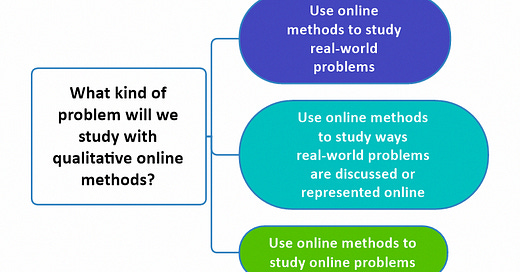

Let’s keep it simple. Do you want to use online methods to study problems that exist in the real world, real-world problems as they are discussed or represented online, or problems in the online world?

Use Online Methods to Study Real-World Problems

Are you interested in studying a problem from the real world, a problem not directly related to technology and digital life? At this point many of us see no boundaries between “online” and the “real world.” We exist in a hybrid style of life with ever-on devices. That said, in some parts of the world (including the mountains of Colorado) connections are not always possible. And regardless of internet availability, people are present in their own embodied lived experiences – and as qualitative social researchers these are experiences we want to understand.

If you want to study the lived experiences of individuals or groups, then you could think about technology as a communication medium. If you call someone on the telephone, you are probably not calling to discuss telephones. You are calling to discuss your kids, job, plans to go to a movie, or whatever is on your mind. The phone is simply a medium for communicating with someone not present physically. In such studies the medium itself is of little concern; we want to use the ICT the participants find accessible and usable.

Use Online Methods to Study How Real-World Problems Are Discussed or Represented Online

Are you interested in studying a problem from the real world, but want to know how that problem is discussed or represented online? When you want to discuss issues about your everyday life from a larger perspective, or find support not available to you, you might log into social media, a group text, or even Substack. The topics aren’t necessarily related to the ICT, you are using the ICT to find others who share your interests or concerns.

As researchers we can learn about the way people experience these online groups, events, or communities by observing or interacting with them. We can also read posts, records, or documents about the problem. We’ll call this option the setting, that is, you are using the ICT as a setting to where you collect data.

Use Online Methods to Study Online Problems

Are you interested in the ICT itself, the features, characteristics, usage and other aspects of it? In this case we aren’t looking at what people discuss online, but how they interact, using the affordances of the tool or platform. In this case the ICT is the phenomenon central to the study.

An Example.

Let’s say you are interested in defining a research problem concerning parenting issues with teenaged children. You might choose to design a study with participants from across your community, country, or across the world. Knowing how busy parents are, you might choose to use online interviews so you can interact with participants when and where it is most convenient. Some parents might prefer the medium of text chat, others might like to meet in a video chat. Since you are not studying the ICT per se, any medium will do.

Perhaps you want to know how and where parents find support online, perhaps looking at specific teen issues like LGBTQ+ identities or schooling. You might decide to find online support groups, counseling groups, or group chats where such conversations occur. These online spaces might be the setting for the study.

Or, maybe you are interested in issues parents have regarding teens and technology, such as social media use, or cyberbullying. In this case you might study the the modes, frequency, and patterns of interaction afforded by the platform. In this case the platform might be both the setting and the phenomenon.

The suggestion here is not to describe the problem in hard and firm categories, but think through the nature of the problem and how it might relate to other parts of the study. In the February newsletter we will dig into ways these decisions relate to the choice of methodology and methods for conducting the study.

Who identifies the problem?

Who decides what problems merit the commitment of time and resources involved in conducting research? Who decides what kinds of outputs to aim for, whether it is a scholarly paper or a manual for practitioners? Are researchers the only ones who can and should identify problems that merit study? What about the people who are experiencing the problem? Should consideration of relevance to the field, to practice, to impactful change-making in the world, be woven into the formulation of research topics and problems?

In the 2007 book Engaged Scholarship: A Guide to Organizational and Social Research, Andrew Van de Ven suggested that we need to engage with the people who have direct first-hand knowledge and experience with the issues and contexts associated with the inquiry. He coined the term “engaged scholarship” and defined it as:

a participative form of research for obtaining the advice and perspectives of key stakeholders (researchers, users, clients, sponsors, and practitioners) to understand a complex social problem. By exploiting differences in the kinds of knowledge that scholars and other stakeholders can bring forth on a problem...engaged scholarship produces knowledge that is more penetrating and insightful than when scholars or practitioners work on the problems alone. (Van de Ven, 2007 p. 9)

Van de Ven’s (2007) approach makes the case for principles of engagement with those who have relevant personal or professional knowledge. He points out that the less you know the greater the need to engage with others who can instruct and ground you in the problem domain (p. 268).

Since 2007 many forms of engaged scholarship have emerged that apply these principles in various fields of study, such as:

Community Engaged Scholarship (CES): researchers and community stakeholders’ contributions, in their respective areas of expertise, co-create knowledge that addresses community-identified cares and concerns, as well as serving the public good (O’Meara, 2018).

Publicly Engaged Scholarship (PES): In fields of public administration and public policy, “scholars have responded to changing demographics within higher education as well as the contemporary demands of societies to address challenging issues of inequality, environmental degradation, and democratic exclusion, among others, by developing less hierarchical and more cooperative forms of scholarship” (Eatman et al., 2018) p. 532.

Van de Ven advocated that these principles should underpin all research methodologies and for this to be an explicit criterion in the establishment of research designs. That said, the degree of engagement might vary greatly. In some cases, it involves meeting and talking with people about issues related to the research problem, or observing the culture, community, or organization. For others it will involve engaging with relevant reports, publications or media by people close to the situation – expanding beyond scholarly literature to gain more accurate descriptions of the problem. Still others recruit people to work hand-in-hand as co-researchers, defining the goals of the study and helping to conduct it. These four categories, adapted from Van de Ven’s descriptions, offer some options:

Informed Research: Research problem is identified and defined with the advice and feedback of stakeholders.

Design/Evaluation Research: Problem is identified and defined by the organization, community, or group who engages the researcher.

Collaborative Research: Research problem is identified and defined by the researcher and project partners.

Participatory Action Research: Research problem, and intentions for interventions or change to address it, are identified and defined by the researcher, partners and co-researchers. Action research, or participatory action research, includes stakeholders in research design, plans, conduct, and dissemination/implementation. Stringer and Ortiz Aragón (2020) introduce their excellent text with this key point: “Action research works on the assumption that those closest to the impact of [contemporary] issues are “experts” in understanding many of the realities of their own lives and should therefore be directly involved in addressing them” (p. 6).

Using the above example about a study into parenting teens, we could say that:

Informed Research: Parents give input and feedback about the problem to study.

Design/Evaluation Research: A parent organization hires the researchers to conduct a study about a problem they defined.

Collaborative Research: The researcher and parents or representatives of a parent organization work together to define the research problem.

Participatory Action Research: Parents are co-researchers at all stages of the study.

The degree of engagement shifts with each of these options, moving from input and feedback to actively sharing responsibilities and decision-making. One is not inherently better than another, the appropriate choice will fit the particular situation. For example, not everyone has the time and resources necessary to build relationships needed for collaborative or action research. However, as researchers, every engagement offers an opportunity to learn from and with those who know, experience, and understand the situation and can thus help define a more relevant problem to study than we might otherwise determine.

Questions to consider to increase engagement at the problem definition stage:

Who understands the domain you want to study, the population, the setting, and/or the culture important to the topic(s) of interest?

Who feels the impact of issues at hand, and who will feel the impact of change?

What do they read: are there publications, blogs, newsletters, reports, or other sources that get into the issues at hand? When you look at these sources, are there respected experts or community leaders who articulate the issues?

Where do people close to the problem share concerns, thoughts, feelings about the issues? Online or local groups?

Do discussions point to other disciplines or literatures you should explore to get a fuller understanding of the problem domain?

If you want to ask for input, feedback, or collaborative involvement, what can you offer in return? Beyond the usual incentives, can you offer to share findings, practical recommendations, training, or other assistance?

Avoid “helicopter” research, coming into a community, taking what you need and then leaving without giving anything back, especially when crossing cultures. See the Global Code Of Conduct For Research In Resource-Poor Settings.

I’ve given you a lot of questions to think about at this beginning point in the process. I hope they help you clarify your focus and get ready to make the next set of choices about methodologies, methods, and importantly how to plan and conduct your study to the highest ethical standards - the topics for the February and March newsletters respectively.

Scroll down for open-access resources about defining the research problem for an online qualitative study.

Dig deeper!

Learn from researchers’ books and interviews.

In the book from Sage Publishing, Critical Participatory Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Guide, co-authors show how action, engaged methods can be used. They include creative and digital methods in a timely book. In this interview co-authors Meagan Call-Cummings, Giovanni P. Dazzo, and Melissa Hauber-Özer define Critical Participatory Inquiry and offer examples.

Julianne Cheek and Elise Øby co-authored the book Research Design: Why Thinking About Design Matters from Sage Publishing. They sat down with me to discuss the decision-making central to designing and conducting research. In this series of recordings they walk through important points covered in each chapter. Two are relevant to this newsletter’s focus: Chapter 1 – Research Design: What You Need to Think About and Why, and Chapter 3 – Developing Your Research Questions.

See my book, Doing Qualitative Research Design (2022), for in-depth explanations of online research design.

Read the literature.

These multidisiplinary open-access articles explore research problem formulation.

Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801

Abstract. This article serves as an introduction to the FQS special issue "Participatory Qualitative Research." Note: link to the entire special issue on participatory methods.

Borg, M., Karlsson, B., Kim, H. S., & McCormack, B. (2012). Opening up for Many Voices in Knowledge Construction. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1793

Abstract. The key epistemological assumption in participatory research is the belief that knowledge is embedded in the lives and experiences of individuals and that knowledge is developed only through a cooperative process between researchers and experiencing individuals.

Chen, S., Sharma, G., & Muñoz, P. In Pursuit of Impact: From Research Questions to Problem Formulation in Entrepreneurship Research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 0(0), 10422587221111736. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587221111736

Abstract. In this paper, we address recent calls to increase the societal relevance of entrepreneurship research. We made two discoveries, as it pertains to the formulation of problems in entrepreneurship research. First, we found four critical change dimensions, along which a problem evolves throughout the research process: worthiness, divisibility, centrality, and specificity. Second, we found two equifinal problem formulation pathways in impact-oriented entrepreneurship research: inward-looking iterative and outward-looking joint problem formulation.

Clark, A. T., Ahmed, I., Metzger, S., Walker, E., & Wylie, R. (2022). Moving From Co-Design to Co-Research: Engaging Youth Participation in Guided Qualitative Inquiry. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221084793

Abstract. The inclusion of community voices in research is important. Over the years, research training programs have continued to emphasize that engagement with communities at the focus of research can promote thoughtful, sensitive designs (Rivera et al., 2004). In this paper, we discuss a method for youth participation in the research process. In an attempt to move beyond “staged and superficial” participation in gathering youth perspectives, we advocate for including co-researchers in the development and modification of fundamental aspects of the research process, from data analysis to the development of additional research questions and collection methods (Guishard & Tuck, 2013).

Jones, P., & Forder, R. (2013). Problem formulation and study design. Keynotes and Extended, 55.

Abstract. This paper provides an overview of principles of Operational Research problem formulation and study design. Problem formulation identifies what the analysis is trying to achieve and what issues it needs to address. The paper examines problem formulation challenges like understanding your customer and stakeholders‟ needs and deciding on study scope.

Mreiwed, H., Wright, L. H. V., & Butler, K. (2024). Deepening our understanding: Collaboration through online peer-to-peer participatory action research with children. Childhood, 31(3), 390-406. https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682241266961

Abstract. Child-led research is growing globally, yet there are still limitations for children’s leadership in all phases of research. This article, co-written with adult and child researchers, examines child-led research undertaken online with 9 children from Ontario and Quebec over a one-year period. The article explores the process of participating in and collaborating on an online peer-to-peer participatory action research project from the brainstorming stage to recruitment, design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination of knowledge.

Pardede, P. (2018). Identifying and formulating the research problem. Res. ELT, 1, 1-13.

Abstract. The first and most important step of a research is formulation of research problems. It is like the foundation of a building to be constructed. To solve a problem someone has to know about the problem. So, the problem identification and formulation is very crucial for the researcher before conducting a research, and this is perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of any research undertaking. The “problem” is stated in the opening passages of a study and, in effect, provides a reader the rationale for why the study is important and why it is necessary to read.

Power, M., Patrick, R., & Garthwaite, K. (2024). “I Feel Like I am Part of Something Bigger Than Me”: Methodological Reflections From Longitudinal Online Participatory Research. International Review of Qualitative Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/19408447241260448

Abstract. This article details methodological reflections and implications for future work from an innovative, participatory research project that started life during the UK’s first COVID-19 lockdown in early 2020. We reflect on the practice, ethical considerations, and challenges of this (necessarily) online participatory research program, which featured intensive, prolonged collaboration with parents/carers living on a low income within the UK.

Sequeira, A. H. (2014). Conceptualization in research. Psychology of innovation ejournal CMBO.

Abstract. Research is always based on reliable data and the methods used to capture this data. Scientific methods facilitate this process to obtain quality output in research. Formulation of research problem is the first step to begin with research. It is at this stage, the researcher should have a clear understanding of the words and terms used in the research such that there are no conflicts arising later regarding their interpretation and measurements. This necessitates the understanding of the conceptualization process.

Shoket, M. (2014). Research problem: identification and formulation. International Journal of Research, 1(4), 512-518.

Abstract. Research is an investigation or experimentation that is aimed at a discovery and interpretation of facts, revision of theories or laws or practical application of the new or revised theories or laws. Identification of research problem leads in conducting a research. To initiate a research, the necessity for the research, to be carried out should be generated.The ideas and topics are developed while consulting literatures, discussions with experts and continuation of activities related to the subject matter.

Verhage, M., Lindenberg, J., Bussemaker, M., & Abma, T. A. (2024). The Promises of Inclusive Research Methodologies: Relational Design and Praxis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241230407

Abstract. This article explores the potential and challenges of inclusive research methodologies when working with older individuals with lower literacy levels. We present inclusive approaches developed during our research and discuss their implications for methodology and individual well-being among older adults with lower literacy levels. Our key insight is that the promise of inclusive research lies in relational design and praxis. Prioritizing meaningful relationships between researchers and participants, we emphasize the importance of considering participants as active contributors rather than mere informants.

Younas, A., Durante, A., & Fàbregues, S. (2024). Understanding the Nature of and Identifying and Formulating “Research Problems” in Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 18(4), 483-502. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898231191441

Abstract. Mixed methods research (MMR) is suitable for studying research problems that cannot be adequately investigated through qualitative and quantitative methods alone. Nevertheless, the MMR literature offers a very limited discussion about “research problems.” To address this gap, this paper uses Elliott’s conceptual framework to offer guidance on how to identify and formulate research problems in MMR and understand their nature.

Yan Zhao, I., Holroyd, E., Garrett, N., Neville, S., & Wright-st Clair, V. A. (2023). Using Co-design Methods With Chinese Late-Life Immigrants to Translate Mixed-Method Findings to Social Resources. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231157704

Abstract. Mainland Chinese born in the 1940s–1950s have experienced unique socio-cultural circumstances that have shaped their late-life immigration experiences. … Eight co-researchers completed three co-design workshops, and two key service providers were consulted. Co-researchers co-designed guidebooks on accessing primary healthcare facilities, social services, aged care facilities, and public transport, which were considered helpful for ameliorating loneliness.

References

Eatman, T. K., Ivory, G., Saltmarsh, J., Middleton, M., Wittman, A., & Dolgon, C. (2018). Co-Constructing Knowledge Spheres in the Academy: Developing Frameworks and Tools for Advancing Publicly Engaged Scholarship. Urban Education, 53(4), 532-561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918762590

Given, L. (Ed.). (2008). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. SAGE Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909.

McCormack, B. (2011). Engaged scholarship and research impact: integrating the doing and using of research in practice. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(2), 111-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987110393419

O’Meara, K. (2018). Accurately assessing engaged scholarship. Inside Higher Education.

Stringer, E. T., & Aragón, A. O. (2020). Action research. SAGE Publishing.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship : A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford University Press.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Thanks to Beth Spencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!