The September newsletter focuses on creative methods. This follow-up post delves into one participatory approach: photovoice.

When designing a study, what kind of questions do we want to pose, to gain what knowledge? This is one of my favorite quotes:

Questions, after all, raise some profound issues about what kind of knowledge is possible and desirable, and how it is to be achieved. For example, do all questions have to be made in words? (Pryke, 2003)

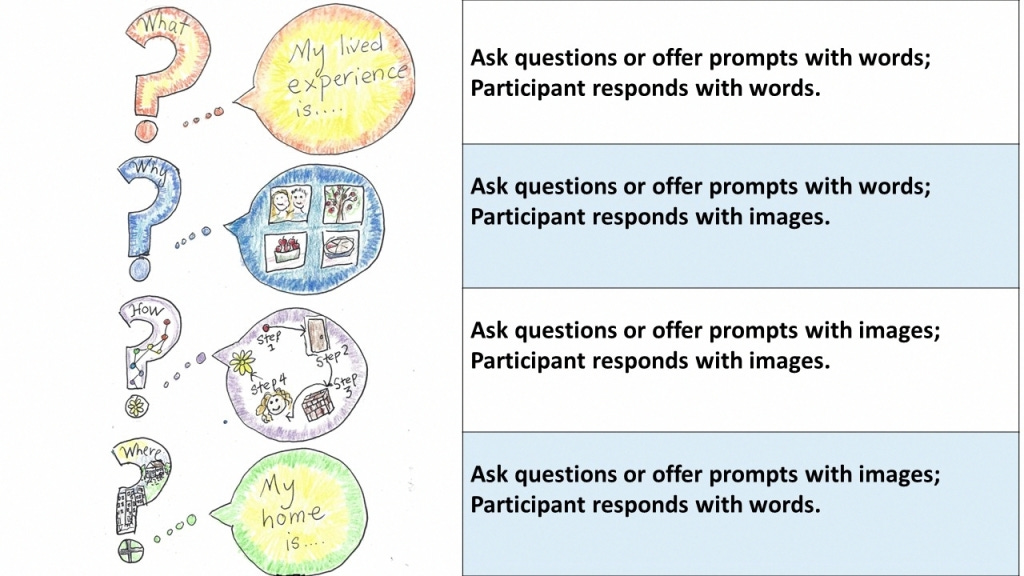

In response to Pryke's challenge, I suggest that we gain more kinds of knowledge when our communication is not limited to words. We can pose questions and elicit responses with words or pictures. Certainly, other creative modes are possible, but for this post we will focus on visuals. The multimedia nature of the Internet means we can use a wide variety of elicitation techniques in online studies; those methods will be discussed in future posts.

Whose images will be used in the study?

The general term visual elicitation is used here to encompass the introduction of any kind of visual material into the interview, including photographs, videos, drawings, artwork, diagrams, or graphics.

When you elicit data by questioning participants, you expect them to recall their experiences and be able to represent them in responses. You hope that their explanations are full and that they have not excluded details they've forgotten or are reluctant to share. With visual elicitation, participants are asked open-ended questions about visuals that depict some aspect of the phenomenon being studied. Prompting a participant with ‘tell me about this photograph,’ for example, shifts the locus of meaning away from descriptive representations of objects, places, people, or interactions. Instead, images gain significance through the way that participants engage and interpret them.

Visual representations of some aspects of the research phenomenon can be generated by the researcher, by the participant, or obtained from extant or other sources. Elicitation in this context refers to research interviews that use visuals to elicit responses and stimulate discussion about participants’ experiences of the research phenomenon. Researchers who want to use visual elicitation must of course decide what visuals fit the study. There are two primary options, and naturally, each has pros and cons:

Images from the researcher: The researcher can take, create, or find photographs or media, diagrams or artworks that depict aspects of the phenomena they want to discuss. The advantage is that the researcher owns the rights or has permission to use these images in publications or presentations without revealing participants’ identities. The disadvantage is that participants might not identify with or relate to the photographs.

Images from the participant: The researcher invites the participants to generate photographs or artwork on a topic or in response to a prompt. Participants can submit the images in advance of the interview or share them during the interview. The interview style is less structured, since each participant discusses their own photos. This means each interview will be unique. The advantage is that the images are personalized to the participants’ experiences and perceptions, so will likely generate a rich discussion. The disadvantage is that when photos show participants and other people, private or protected settings, they cannot be used in publications without jeopardizing anonymity. Artwork might be the property of the participant.

What is Photovoice?

Photovoice is a qualitative methodology that involves participant-generated photos, sometimes accompanied by written annotations or comments. Jean Breny and Shannon McMorrow, co-authors of Photovoice for Social Justice: Visual Representation in Action, define this approach:

Photovoice is a powerful qualitative research method that combines photos and accompanying words generated by participants. Developed nearly three decades ago as a participatory research method in public health by Wang & Burris (1994, 1997), it has since evolved for use worldwide, across numerous academic disciplines, and by a variety of practitioners working with communities for change, advocacy efforts, and social justice. As a participatory research method, each project evolves a bit differently based on a variety of factors including, but not limited to funding, goals of participant/co-researchers, goals of researchers or community project leaders, questions at hand, and local context. A core component of Photovoice is some sort of culminating component focusing on advocacy and/or policy change. An overarching snapshot of the photovoice implementation process is a series of modified focus groups where participants meet to engage in ethics and safety training around taking photos, discussions of photos taken, shared analysis of photos, and shared planning for an advocacy event. Photovoice has traditionally been implemented in person, in community-based settings, but as with so many other research methods, it can be modified for use both in person or online.

McMorrow and Breny identified key questions for researchers considering a photovoice study:

What is your capacity to store, organize, and manage the textual data and photos?

How long do you have to analyze the data?

What sources of data do you and the participants/co-researchers feel would be useful for advocacy purposes?

What sources of data do you and the participants/co-researchers feel would be useful for other dissemination such as social media, academic presentations or publications, or community reports?

Want to learn more? These two books provide important foundations.

Learn from experienced, respected researchers and creative methodologists Nicole Brown, Jean Breny and Shannon McMorrow:

Photovoice Reimagined This indispensable ‘how-to’ book with exercises and visual aids takes novice and veteran researchers through the practicalities and ethics of applying this approach. Written by experienced teacher and creative researcher, Nicole Brown.

Photovoice for Social Justice Jean M. Breny and Shannon L. McMorrow approach photovoice as not only a community-based participatory research method, but as a method for social justice, centering community participants, organizations, and policy makers at the heart of this research method.

Open-Access Articles

If you have additional articles, examples, or resources about visual elicitation or photovoice please add them in the comments area.

Bailey, K. A., Dagenais, M., & Gammage, K. L. (2021). Is a Picture Worth a Thousand Words? Using Photo-Elicitation to Study Body Image in Middle-to-Older Age Women With and Without Multiple Sclerosis. Qualitative Health Research, 31(8), 1542–1554. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323211014830

Abstract. In this study, we explored how women with varying relationships to disability and aging used photographs to represent their body image experiences. Seven middle-aged and older adult women with and without multiple sclerosis were asked to provide up to 10 photographs that represented their body image and complete a one-on-one interview. We used reflexive thematic analysis to develop themes and interpret the findings. Overall, the women expressed not only complicated relationships with their bodies, represented through symbolism, scrutiny of body features (e.g., posture, varicose veins, and arthritis) but also deep reflection linked to positive body image and resilience. These findings revealed not only the nuanced experiences women have with aging, disability, and gender but also the commonly experienced ingrained views of body appearance as each participant illustrated a difficult negotiation with the aesthetic dimension of their body image. Finally, we provide important implications of the use of visual methods in body image research.

Epstein, I., Stevens, B., McKeever, P., & Baruchel, S. (2006). Photo Elicitation Interview (PEI): Using Photos to Elicit Children’s Perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500301

Abstract. When conducting photo elicitation interviews (PEI), researchers introduce photographs into the interview context. Although PEI has been employed across a wide variety of disciplines and participants, little has been written about the use of photographs in interviews with children. In this article, the authors review the use of PEI in a research study that explored the perspectives on camp of children with cancer. In particular, they review some of the methodological and ethical challenges, including (a) who should take the photographs and (b) how the photographs should be integrated into the interview. Although some limitations exist, PEI in its various forms can challenge participants, trigger memory, lead to new perspectives, and assist with building trust and rapport.

Hannes, K., & Parylo, O. (2014). Let’s Play it Safe: Ethical Considerations from Participants in a Photovoice Research Project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300112

Abstract. The use of images and other visual data in qualitative research projects poses new ethical challenges, particularly in the context of participatory research projects that engage research participants in conducting fieldwork. Little is known about how research participants deal with the ethical challenges involved in conducting fieldwork, or whether they succeed in making balanced ethical judgments in collecting images of identifiable people and places. This study aims to increase our understanding of these ethical challenges. From an inductive analysis of interview data generated from nine participants recently involved in a photovoice research project we conclude that raising awareness about ethical aspects of conducting visual research increases research participants' sensitivity toward ethical issues related to privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality of research subjects. However, personal reasons (e.g., cultural, emotional) and cautions about potential ethical dilemmas also prompt avoidance behavior. While ethics sessions may empower participants by equipping them with the knowledge of research ethics, ethics sessions may also have an unintentional impact on research.

Kyololo, O. M., Stevens, B. J., & Songok, J. (2023). Photo-Elicitation Technique: Utility and Challenges in Clinical Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231165714

Abstract. Photo-elicitation interview techniques, a method in which researchers incorporate images to enrich the interview experience, have been gaining traction in numerous spheres of research over the last two decades. Little is, however, written about the utility of the technique in studies involving vulnerable populations in clinical contexts. Drawing on research where researcher-generated photographs were used to elicit mothers’ experiences of pain and perceptions about use of pain-relieving strategies in critically ill infants, we aim to demonstrate (a) how the method can be used to generate harmonized and detailed accounts of experiences from diverse groups of participants of limited literacy levels, (b) the ethical and methodological consideration when employing photo-elicitation interview techniques and the (c) possible limitations of employing photo-elicitation interview techniques in clinical research.

Liebenberg, L. (2018). Thinking Critically About Photovoice: Achieving Empowerment and Social Change. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918757631

Abstract. Photovoice, as a community-based participatory action research (PAR) method, has gained immense popularity since Wang and Burris first introduced it in the early 90s, originally as “photo novella.” Developed as a component of their work with women living in rural farming communities of Yunnan province China, Wang and Burris used this method to assess women’s health and socioeconomic needs, in an effort to support improved reproductive health outcomes. Wang and Burris (1994, p. 179) explain that the purpose of photovoice “was to promote a process of women’s participation that would be analytical, proactive, and empowering.” It is undoubtedly the benefits this method provides to researchers, participants,1 and their communities2 as well as other stakeholders (such as service providers and policy makers) who have driven its popularity.

Mark, G., & Boulton, A. (2017). Indigenising Photovoice: Putting Māori Cultural Values Into a Research Method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(3). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.3.2827

Abstract. In this article, we discuss Indigenous epistemology that ensures research is inclusive of Māori cultural values, such as collectivity and storytelling. We explain an adapted photovoice methodology used in research investigating Māori (the Indigenous peoples of Aotearoa/New Zealand) patient's perspectives on rongoāMāori (traditional Māori healing) and primary health care. Traditional photovoice theoretical frameworks and methodology were modified to allow Māori participants to document and communicate their experiences of health and the health services they utilised. Moreover, we describe the necessity for cultural adaptation of the theoretical framework and methodology of photovoice to highlight culturally appropriate research practice for Māori.

Marshall, A. N., Walton, Q. L., Eigege, C. Y., Daundasekara, S. S., & Hernandez, D. C. (2023). Comparing In-Person and Online Modalities for Photo Elicitation Interviews Among a Vulnerable Population: Recruitment, Retention, and Data Collection Applications. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231205794

Abstract. The purpose of the current study was to use Orsmond and Cohn’s feasibility framework to compare two methods of collecting photo elicitation interviews: (1) in-person and (2) online among low-income community college students. We described the feasibility of the recruitment and retention procedures and compared the participants’ characteristics and the type of data obtained by data collection modality. Focus group participants (n = 34) were invited to participate in photo elicitation interviews regarding barriers to food access and associated material hardships. Prior to the pandemic, photo elicitation interviews were conducted in-person. Due to pandemic-related stay-at-home policies, photo elicitation interviews shifted to a video conferencing platform. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were used to compare the two data collection methods in terms of sample characteristics, the average length of each interview, and the number and type of photos submitted.

Platzer, F., Steverink, N., Haan, M., de Greef, M., & Goedendorp, M. (2021). The Bigger Picture: Research Strategy for a Photo-Elicitation Study Investigating Positive Health Perceptions of Older Adults With Low Socioeconomic Status. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211040950

Abstract. Research focusing on older adults of low socioeconomic status (SES) faces several methodological challenges, including high rates of non-response and drop-out. In addition, older adults of low SES tend to be less willing to participate in research and are more likely to experience cognitive impairments and literacy problems. Photo-elicitation studies do not require high levels of literacy, and they might therefore be suitable for use in research with older adults of low SES. To date, however, little is known about setting up such studies with this target group. Our aim was to demonstrate how we systematically set up a researcher-driven photo-elicitation study to generate greater insight into the positive health perceptions of older adults of low SES. Our strategy consisted of three phases: development, testing and execution. In this article, we discuss each step of the research strategy and describe the limitations and strengths of our study. We also formulate recommendations for further research using photo-elicitation methods with this target group. Based on the results of this study, we conclude that the use of researcher-driven photo-elicitation is a powerful tool for enhancing understanding with regard to positive health perceptions and experiences of older adults of low SES. The usefulness of the method is particularly dependent on the careful development and testing of the study.

Sprague, N. L., Okere, U. C., Kaufman, Z. B., & Ekenga, C. C. (2021). Enhancing Educational and Environmental Awareness Outcomes Through Photovoice. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211016719

Abstract. In the United States, there are substantial barriers to youth nature access and environmental education (EE). These barriers may lead to racial, geographic, and socioeconomic disparities in both nature contact and environmental awareness. This study investigated the impacts of a Photovoice EE intervention on the environmental perceptions, STEM-capacity, and environmental awareness of 335 low-income, urban youth (ages 9–15). Youth were assigned to one of two intervention groups, a Photovoice EE intervention group or an EE intervention group without a Photovoice activity, or a control group. The Photovoice activity revealed that participants perceived the environment in three major subthemes: social, natural, and built.

Switzer S, Flicker S. Visualizing DEPICT: A Multistep Model for Participatory Analysis in Photovoice Research for Social Change. Health Promotion Practice. 2021;22(2_suppl):50S-65S. doi:10.1177/15248399211045017

Abstract. As a critical narrative intervention, photovoice invites community members to use photography to identify, document, and discuss issues in their communities. The method is often employed with projects that have a social change mandate. Photovoice may help participants express issues that are difficult to articulate, create tangible and meaningful research products for communities, and increase feelings of ownership. Despite being hailed as a promising participatory method, models for how to integrate diverse stakeholders feasibly, collaboratively, and rigorously into the analytic process are rare. The DEPICT model, originally developed to collaboratively analyze textual data, enhances rigor by including multiple stakeholders in the analysis process. We share lessons learned from Picturing Participation, a photovoice project exploring engagement in the HIV sector, to describe how we adapted DEPICT to collaboratively analyze participant-generated images and narratives across multiple sites. We highlight the following stages: dynamic reading, engaged codebook development, participatory coding, inclusive reviewing and summarizing of categories, and collaborative analysis and translation, and we discuss how participatory analysis is compatible with creative, interactive dissemination outputs such as exhibitions, presentations, and workshops. The benefits of Visualizing DEPICT include feelings of increased ownership by community researchers and participants, enhanced rigor, and sophisticated knowledge translation approaches that honor multiple forms of knowing and community leadership. The potential challenges include navigating team capacity and resources, transparency and confidentiality, power dynamics, data overload, and streamlining “messy” analytic processes without losing complexity or involvement. Throughout, we offer recommendations for designing participatory visual analysis processes that are connected to critical narrative intervention and social change aims.

Trevenen-Jones, A. (Ann), Cho, M. J., Thrivikraman, J., & Vicherat Mattar, D. (2020). Snap-Send-Share-Story: A Methodological Approach to Understanding Urban Residents’ Household Food Waste Group Stories in The Hague (Netherlands). International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920981325

Abstract. Rich understandings of the phenomenon, urban household food waste (HFW), are critical to realizing the vision of sustainable, inclusive human settlement. In 2018/19, an exploratory study of HFW perceptions and practices of a diversity of urban residents, was conducted in the Bezuidenhout neighborhood, The Hague (Netherlands). Nineteen participants, communicating in one of three languages, as per their preference, participated through-out this visually enhanced study. The sequential “Snap-Send-Share-Story” qualitative, participatory action research (PAR) inspired methodology, employed in the study, is introduced in this paper. Focus groups (“Story”) which resourced and followed photovoice individual interviews (“Snap-Send-Share”) are principally emphasized. Three focus groups were conducted viz. Dutch (n = 7), English (n = 7) and Arabic (n = 5), within a narrative, photo elicitation style. Explicit and tacit, sensitive, private and seemingly evident yet hard to succinctly verbalize interpretations of HFW—shared and contested—were expressed through group stories. Participants accessed a stream of creativity, from photographing HFW in the privacy of their homes to co-constructing stories in the social research space of focus groups. Stories went beyond the content of the photographs to imagine zero HFW. This approach encouraged critical interaction, awareness of HFW, reflexive synthesis of meaning and deliberations regard social and ecological action.

Wang, Q., & Hannes, K. (2020). Toward a More Comprehensive Type of Analysis in Photovoice Research: The Development and Illustration of Supportive Question Matrices for Research Teams. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920914712

Abstract. In this article, we present a comprehensive approach to analysis to assist researchers in conducting and analyzing photovoice studies. A screening of primary studies in four systematic reviews focusing on photovoice research revealed that the focus of analysis of researchers is the narrative provided with the photos from the participants, which undermines the potential of the photos themselves to provide meaning. In addition, the analytical effort of photovoice researchers is often limited to the interpretive phase in their projects. The question matrices we developed facilitate photovoice researchers who aim to give more weight to photos as an interpretive medium and wish to extend their analytical lens to different phases of a research cycle. They focus our analytical attention on three different sites—site of production, site of photo, and site of audiencing, and three different modalities—technological modality, compositional modality, and social modality. The matrices are designed to present an overview of the important dimensions that researchers might need to take into account when conducting photovoice research studies. We provide relevant examples to illustrate the potential risks and benefits of the analytical choices we make. Photovoice researchers should increase their awareness of the impact of our choices on the analytical process and avoid the analytical strategies that may disempower participants and reproduce existing power relationships.

Zhang, Y., & Hennebry-Leung, M. (2023). A Review of Using Photo-Elicitation Interviews in Qualitative Education Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231185456

Abstract. Educational research has sometimes been criticized for its seeming lack of relevance to classroom reality and its subsequent inability to inform pedagogical practices. Such criticism has prompted researchers to consider research methods that may better approximate reality. Among these methods, photo-elicitation interviews (PEI) offer a visual dimension to elicit lived experiences, feelings, and thoughts in real educational contexts, and to enhance researchers’ understanding of educational practitioners’ and students’ experiences in real classrooms and school communities. This review examines the application of PEI to explore educational practitioners’ and students’ lived experiences and perceptions in educational contexts. Specifically, this paper examines the existing educational studies adopting PEI in order to identify the affordances of the method, the challenges it has presented for researchers in the education field, and critical considerations for researchers who may be planning to use the method. Specifically, this review addresses the following three questions: 1. What has PEI contributed to previous investigations of participants’ lived experiences and perceptions in educational contexts? 2. What methodological challenges have previous researchers encountered when utilizing PEI? and 3. How can methodological concerns be addressed when designing and implementing PEI to understand participants’ lived experiences and perceptions? We provide an up-to-date critical examination and discussion of PEI to better inform researchers seeking to develop the use of the method in future investigations in the education field.

Image by Dariusz Sankowski from Pixabay