Reflexivity in Practice

Reflecting on Reflexivity

I’m continuing to reflect on reflexivity in these last few days of April, before shifting to the May topic about planning and conducting online interviews for qualitative research.

I shared some definitions and discussed types of reflexivity in the newsletter offered earlier this month. Here I’d like to expand on those ideas and discuss ways to put them into practice as a qualitative researcher, journalist, or writer who uses information and communications technologies to collect data.

As discussed, Walsh (2003) and Archer (2003, 2010), each offered four types of reflexivity. I’d like to build on their ideas and separate out the what, the who and the how:

What questions drive your reflexivity?

Who is involved in the process?

How do you put reflexivity into your research practice?

What questions drive your reflexivity?

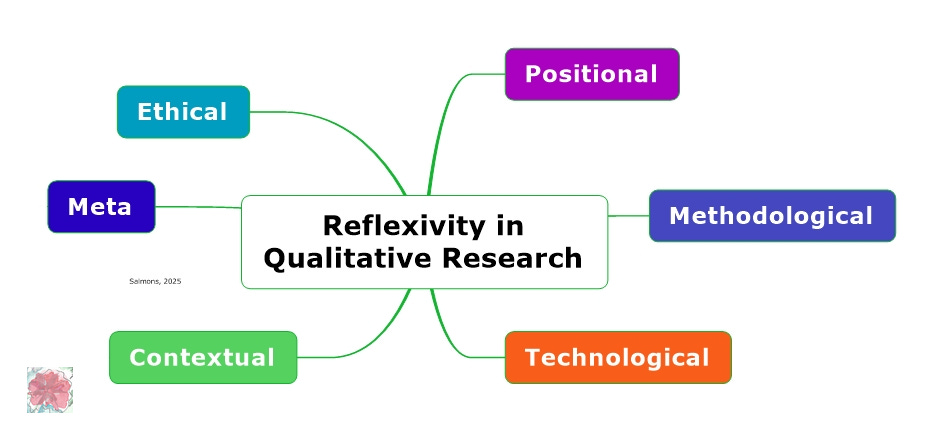

Let’s use this broad definition of reflexivity that describes “a form of critical thinking which aims to articulate the contexts that shape the processes of doing research and subsequently the knowledge produced”(Lazard & McAvoy, 2020, p. 160). A simplistic description: when we reflect, we remember and contemplate our experiences. When we use reflexivity, we delve into those experiences to critique, analyze, and understand them. We can look at our research experiences from a number of angles. Depending on the nature of the nature of the project, here are five inter-related areas ripe for reflexive thinking:

These suggestions will get you started!

Positional reflexivity:

What is our role as researchers, in relation to the problem being investigated and the people, cultures, places, communities, language, or other contextual factors? Are we insiders who are familiar with the issues and contexts, or outsiders with little or no prior knowledge or experience? In any case, what assumptions, expectations, or biases merit thought and reflection? (Note: positionality will be our focus in September.)Methodological reflexivity: Walsh (2003) and Olmos-Vega et al. (2018) note the importance of stepping back to critically evaluate methodological choices, ensuring these decisions align with the research paradigm and theoretical framework. Methodological reflexivity for qualitative social researchers might be more personal since we are the instruments. We might want to critically reflect on how we will develop and use the skills, abilities, and attitudes necessary to successfully implement a study using the selected methodology. A study that involves interviewing refugees from a war zone will call on a different mind- and skillset than one that involves reading diaries.

Technological reflexivity: How do our choices of information and communications technology tools and platforms influence the ways we interact with co-researchers or participants? What do we need to know to use them most effectively, to communicate in ways that build rapport and trust? Paulus and Lester (2023) wrote an excellent must-read article that explains how to think reflexively about the technologies we select for research purposes. They note that “as part of a digital research workflow, then, we should continually examine our technological choices alongside their consequences – be they intended and anticipated, or perhaps unanticipated ones that become visible only over the course of the research study” p. 4.

Contextual reflexivity: Walsh (2003) suggests that we reflect on ways cultural and historical contexts shape the research questions, data collection, and our interpretations. Decolonialism, for example, involves reflecting on specific historical contexts. Contextual reflexivity could also mean thinking about how we fit (or don’t fit) into the research setting, considering the best way to deal with power dynamics, or reflecting on how we present ourselves.

Meta reflexivity: Archer (2003, 2010) says reflexive critique refers to the subjects we direct at our own internal conversations. This is where we consider the big-picture concepts and frameworks, the ontological and epistemological viewpoints that underpin our study. We reflect on how research experiences relate to or challenge assumptions, beliefs, or values.

Ethical reflexivity: At every stage of the process, from problem formulation through publication, we must reflect on our roles and responsibilities as researchers. Am I being honest, respectful, and transparent with colleagues, gatekeepers, co-researchers and participants? (See this newsletter on Ethics in Visual and Creative Methods.)

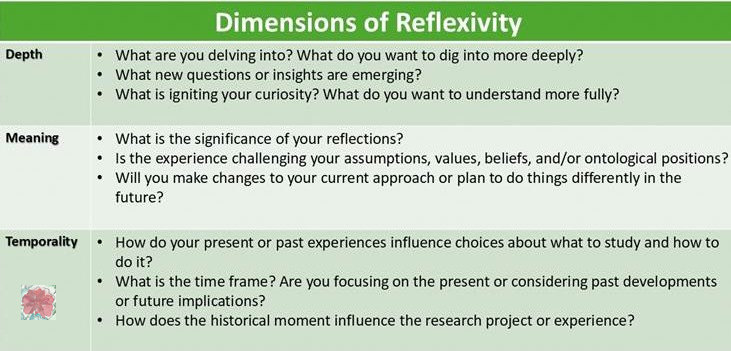

Reflexivity can go in very different directions depending on what dimension(s) of the research experience we want to explore. I’ve adapted three of the dimensions suggested by Ira Progoff (1992): are we looking for more depth or more meaning when we think reflexively? How do we deal with situations where our experiences or observations counter what we thought we knew or believed? What temporal factors influence our interpretations? When we focus on the present study, do incidents from our own past come into play? Do economic, political, or cultural factors of the past or present influence our thinking? Do anticipated future events figure into our interpretations? Here are some more questions to consider:

Clearly, if we explored every possible angle of our research, we would get nothing else done! That said, I hope that these suggestions offer potential directions to explore.

Who is involved in the reflexive process?

Archer, (2003, 2010) wrote about reflexivity in decision-making. She describes autonomous reflexivity as self-contained inner dialogues that lead directly to action without the need for validation by other individuals. We have the autonomy necessary to act based on what we learn from our reflexive process. In a research context, we could say this means we do not need to submit our reflexive writing for supervisory approval or peer review.

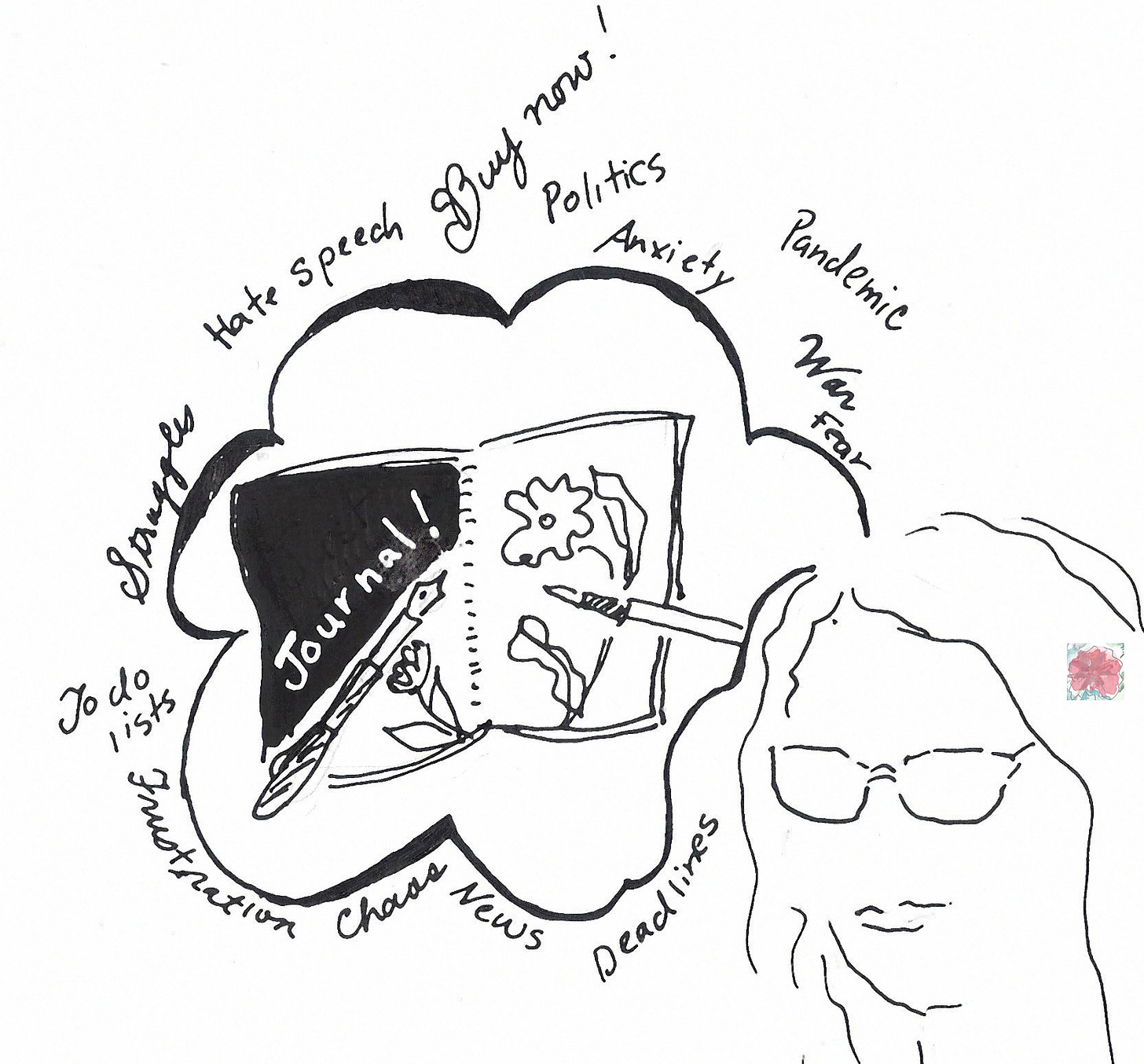

Beyond autonomous reflexivity to record and manage the research project, this kind of personal reflection is also important for self-care. We are often in stressful situations, difficult research settings, or sad circumstances with troubled participants. Reflexivity then is part of our self-care. Our means not only to understand what is going on, but perhaps to escape from it. No matter how diligent and responsible we are about the project, mental time away is refreshing and rejuvenating.

When we do need others’ input, we use what Archer describes as communicative reflexivity: internal conversations that require confirmation by others before resulting in specific courses of action. Walsh (2003) names interpersonal reflexivity that focuses on relationships within the research team and between researchers and participants influence the study. We’ll use the term collaborative reflexivity to describe critical exchanges, discussions, or debriefs with others involved in the study.

While nothing is ever cut and dried, perhaps we can say that autonomous, personal reflexivity is well-suited to the meta levels of reflexivity, when we are looking for depth and meaning in our research experience. This individually-oriented approach might fit when we are reflecting on our positionality, and on our evaluation of ethical decisions and risks. Collaborative reflexivity might be well-suited to methodological, contextual, or technological reflexivity, when input of others with more experience or expertise might be helpful. There are no hard and fast rules; do what makes sense in relation to your needs and the nature of your research project.

Who can access, read, or discuss your reflexive outputs?

Whether the reflexive process is autonomous or collaborative, we need to decide whether the process, and/or outputs of the process, are public or private. Will you share your thinking online, in articles or blog posts, academic papers or dissertations? Or is this process private and personal, to serve your own purposes?

I do both public and private acts of reflexivity. I lead a writing and discussion group – I don’t need their reviews or approvals; we communicate to support and affirm each other. I share some writing and images that emerge from my reflexive practice and keep some private. Do what works for you!

How do you put reflexivity into your research practice?

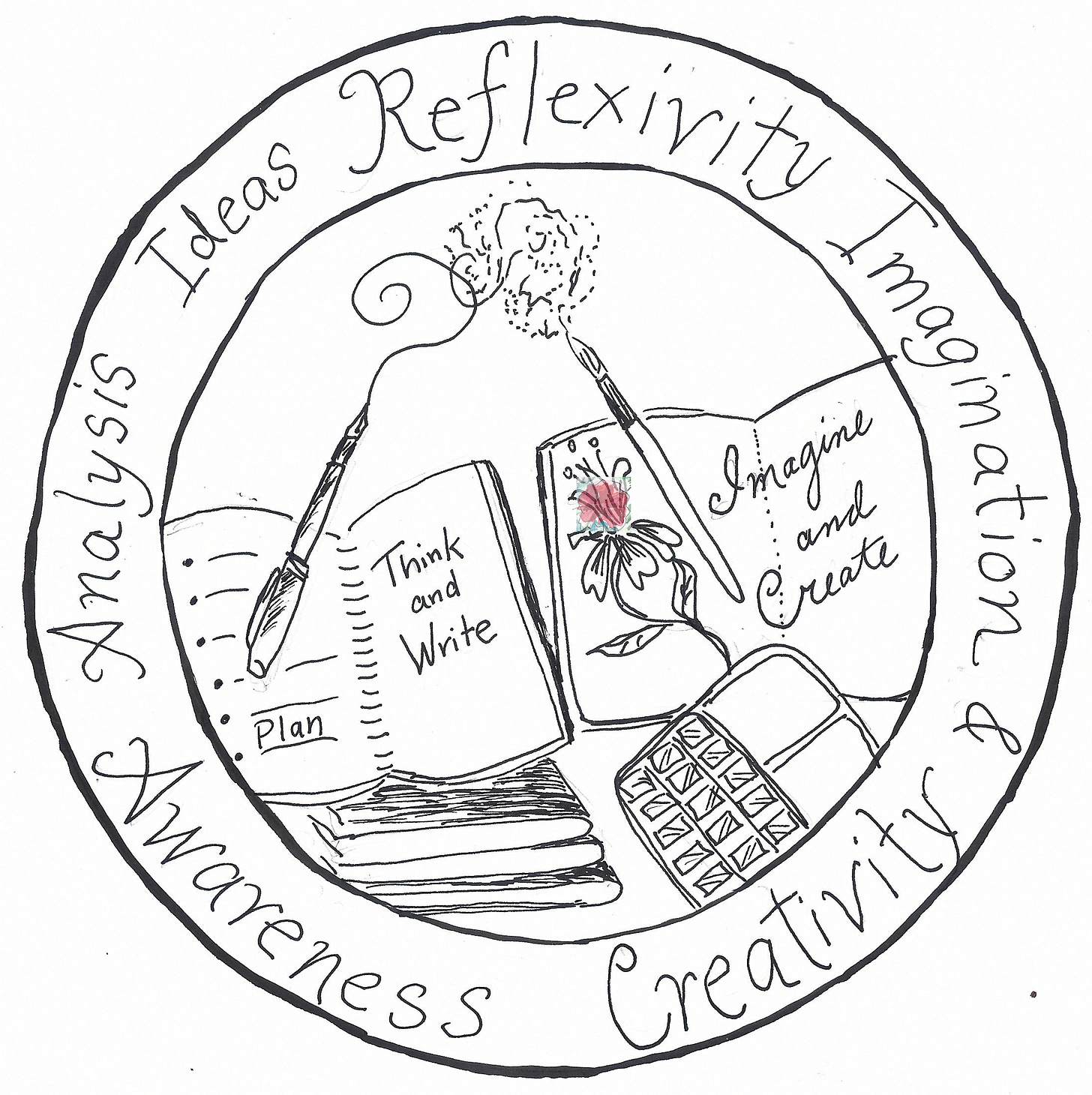

Now we get to the fun part! Journaling is an important option for reflexive practice. Journals can be autonomous or collaborative, public or private. Bacon (2014) notes, the research journal is “a flexible instrument of personal and scholarly insights. Journaling informs the mapping of self and research (Bacon, 2014, p. 1). Insights can be “mapped” in writing or visually. Shields points to the journal as occupying spaces between doing research, writing it up, and publishing it

I use the phrase “journaling right and left” (2023) to describe reflexive journaling practices. Left-brain journaling allows us to stay organized and to manage the myriad details associated with projects that involve multiple stages over a period of time. We create records and critique key experiences and plans in ways that help us feel confident about moving forward. Right-brain journaling allows us to record perceptions of ourselves in our roles as researchers. We can also tap our affective side and creatively express thoughts and feelings.

One way to journal “right” is with art or visual journaling. When we draw or otherwise capture our perceptions we sharpen observation skills so beneficial to qualitative researchers. Shields explains their experience with visual research journaling:

I found myself using the visual journal to make sense of ideas and concepts…This is the movement of research, both making sense of and making visible; however, in traditional research we are often first making sense of and then through our writing making our understanding visible. As an arts-based practice for researchers to engage in, I believe the power of the visual journal is the opportunity to engage in practice that works through both of these processes together. (p. 181)

Nicole Brown, in her excellent book Making the most of your research journal (2021), observes that:

The purpose of art journaling is not necessarily to develop work or ideas, but to record what happens in the moment, as a form of commentary or memory-making and memory-keeping. (p. 7)

She notes the value of journaling when we need to step away from the work of a research project:

Even though seasoned journalers talk about the therapeutic and cathartic properties of journaling, journaling does not need to be therapeutic in its intention. It may simply be an act of meditation. (p. 7)

Journaling can be a mindful retreat, so we can return to our work refreshed and ready to move forward.

Analog or Digital

Online research and digitally intense lives call for a balance. Distractions of online life call for reflexive analog activities. At the same time, when we need to cut and paste into other documents and share, we need to write on computers.

I use a hybrid approach including a digital calendar and a paper planner journal, digital notes and paper written and art journals. I don’t typically retain paper planner pages, once everything on a list is crossed off, I recycle it and start on a fresh page. Notes are typically written on the computer. While my journals represent autonomous reflexivity, some are public and some are private. Just yesterday Substack writer John Halbrooks wrote about his own decisions about how he uses analog and digital options for note-taking.

Digital tools:

Some diary or journal applications are free, others require a subscription. Characteristics of and options for an electronic journal include:

Simple entry: Is it easy to set up and use? If adding a journal entry takes time and effort, you probably won’t keep a regular practice with it.

Varied entries: Can you enter images, drawings or photos, audio, or video, as well as writing? Can you use voice-to-text or capture online pages or posts?

Drawing tools: If using a tablet with a stylus, can you include sketches?

Shared or private options: Will you share journal entries with collaborative partners, co-researchers, students, followers, or keep it private?

Visually appealing layout: Does it offer an attractive, pleasant experience for journaling?

Sync across computers and devices: Can you keep your journal up-to-date regardless of the device you use? You might want the ability to capture thoughts or images on the go, then spend more time when you have a keyboard for more substantive writing.

Daily reminders or prompts: Are there options for reminders, either built-in or customized by you, to help you stay engaged?

Organizational features: Does It offer checklists, templates, or other ways to manage your entries?

Privacy: Can you protect against hackers or scrapers?

Analog supplies:

Paper that fits your entries: If you are planning entries based on writing, you might want lined paper. If you want to mix writing and drawing, you might want dot or graph paper. If you want to use your journal primarily for drawing and painting, you will want blank pages.

Suitable paper weight: Many journals come with paper intended for written entries, and some are adequate only for pencils, ballpoint, or roller ball pens. If you want to do more than that, you will need to take care and selecting the proper paper. Fountain pens do not work well on coated or shiny paper or paper that feathers and bleeds. Choose a journal that is fountain pen friendly and if labeling is not clear, look up the brand or ask knowledgeable shopkeeper.

When you are using your journal for artistic purposes, the weight of the paper becomes an important consideration. If you want to mix written entries with sketches pen and ink, pastels, graphite or colored pencil drawings, a journal labeled as “sketch paper” will work. Sketch paper can range from 50 – 80 lbs, (approximately 75- 90 gsm.). If you want to add light washes and/or collage, then select paper labeled as “mixed media.” Mixed media paper can range between 90-110 lbs. (approximately 180-260 gsm.). However, if you want to do more water media, you will find that pages will wrinkle and buckle, and the journal will not lay flat. If you want to include watercolor as part of your journaling practice, then you need to select watercolor paper, which is usually at least 130 or 140 lbs. (approximately 300 gsm.)Binding that fits your style: Do you want to keep a journal with entries in chronological order? A spiral or hardbound journal allows you to keep all of the pages together so you can see how entries evolve over a period of time. In addition to chronological entries, you can use a bound journal for a more specific topic or theme. For example, you might want a journal dedicated to your entries from field work on location. If you want the ability to add or rearrange pages or add different kinds of paper: lined paper for writing, and art paper for drawing and painting, select a loose-leaf type of journal.

Resources (and discounts!)

If you would like to purchase digital versions Sage books, including Doing Qualitative Research Online, use the discount code UK25BOOKS on the ebooks.com page. You might be interested in Reflexive Narrative: Self-Inquiry Toward Self-Realization and Its Performance, by Christopher Johns (2020), Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research by Mats Alvesson, Kaj Sköldberg (2017), or Reflexivity: The Essential Guide by Tim May, Beth Perry (2017).

Check out Making the most of your research journal by Nicole Brown, with related resources.

A separate email to paid subscribers will include a pdf of the chapter “Journaling right and left” as well as additional worksheets and resources. Note that this newsletter and the archives will always be free and open.

Ready to be reflexive?

There is no right or wrong answer – find the mix of reflexivity types and practices that works for you. Experiment, play, and find the style and process that you find beneficial. Choose something that you can do consistently.

Please use the comment area to share the tools or approaches you find useful and share any resources that might benefit other readers.

References

Archer, M. (2003). Structure, agency, and the internal conversation. Cambridge University.

Archer, M. S. (2010). Conversations about reflexivity. Routledge London.

Bacon, E. (2014). Journaling-a path to exegesis in creative research. Text Journal, 18(2).

Brown, N. (2021). Making the most of your research journal. Policy Press.

Paulus, T. M., & and Lester, J. N. (2024). Digital qualitative research workflows: a reflexivity framework for technological consequences. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 27(6), 621-634. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2023.2237359 (Request full-text here.)

Progoff, I. (1992). At a journal workshop. Putnam.

Salmons, J. E. (2023). Journaling right and left. In N. Lemon (Ed.), Creative Expression and Wellbeing in Higher Education. Routledge.

Shields, S. K. S. (2014). In pursuit of hermeneutic visual journaling: Conceptualizing the visual journal as both a mode and method of inquiry University of Georgia].

Walsh, R. (2003). The methods of reflexivity. The Humanistic Psychologist, 31(4), 51-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2003.9986934

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. In other words, you can use and share but please do NOT have my permission to upload the newsletter or art to AI.

Thanks to Beth Spencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!