In January’s newsletters I invited you to think about what problem merits research. Now we’ll look at ways to align qualitative methods with research problems. In this series of newsletters, from now through June, we will focus on decisions researchers make when designing and conducting studies using methods for collecting data from human participants using information and communication technologies. I hope you will find these materials useful!

Linear Writing about a Circular Process

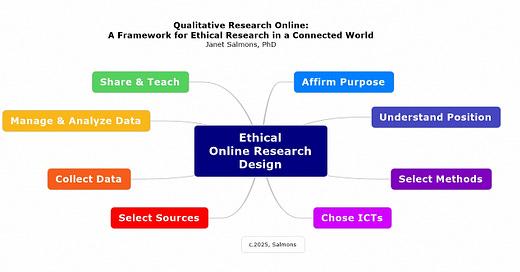

Qualitative research design is not a linear. While there are steps to take, they don’t occur in a predictable sequence. As an online researcher, you will have many decisions to make when designing a study that will involve collecting data on the Internet or with digital tools. While it is true that all researchers face daunting design challenges, distinctive characteristics about how people interact and behave online mean there are additional factors to consider when designing any study that will be entirely or partially conducted online. Given that this is the case, I’ve designed a circular research framework.

The Ethical Online Research Framework offers a conceptual schema of qualitative online research that will help you think through the components of the study, and present it in a coherent way.

The design of this framework, introduced in the 2012 Cases in Online Interview Research, has evolved over time. I updated materials for the 2022 book Doing Qualitative Research Online and continued to refine it during my recent fellowship at the Center for Advanced Internet Studies. I’m currently writing a multimedia design guide which will be published in 2025. The central principle of this framework hasn’t changed: qualitative research design is a recursive, iterative process.

In this post we’re exploring data collection methods in qualitative studies conducted online. First, let's define our terms:

Methodology refers to the philosophies and systems of thinking that justify the methods used to conduct the research. The methodology is a framework that explains why you are conducting the study.

Method refers to the systematic and practical steps used to conduct the study. You choose methods for collecting data, and methods for analyzing and interpreting data.

Sometimes the terms methodology and method are used interchangeably. However, it is useful to differentiate the why, or methodology, and the how, or the methods used to conduct the inquiry. Subscribe to receive future posts that examine decisions about other parts of the research design process.

Data Collection Methods

Popular qualitative methods for data collection include:

Interviews. The researcher poses questions or suggests themes for conversation with research participants. Interviews can be one-one or between a researcher and a small group. Research participants respond to questions and any follow-up prompts. The exchange is recorded and/or the researcher takes notes during the interview. Transcripts of the interview together with researchers’ notes are the data analyzed and interpreted to answer the research questions.

Focus Groups. The focus group typically consists of a group of participants and a researcher who serves as the moderator for discussions. In focus groups, instead of questions and answers between the researcher and the group as happens with an interview, the researcher invites interchange and responses among group members.

Observations. Researchers using observations to collect data take note of whatever may be occurring that relates to the topic of the inquiry. Researchers create guides to help define what to observe. Research observations can take place in a controlled or laboratory setting; naturalistic observations can occur anywhere. Depending on the type of observation, the researcher may or may not engage with those being observed.

Arts-based and Creative Methods. Researchers organize and facilitate opportunities for participants to express perceptions and experiences using artistic forms. See previous posts about creative methods online: Creative Methods in Online Qualitative Research, More Creative Research Methods, and Analyzing Visual and Video Data.

Document or archival analysis. Historical or contemporary documents and records of all kinds are analyzed in this type of qualitative research. The term documents may also refer to diaries, narratives, journals, and other written materials. See previous posts to learn about archival methods online: Archival Methods for Online Researchers and Find open-access scholarly journals in the social sciences.

Align Methods with Problems

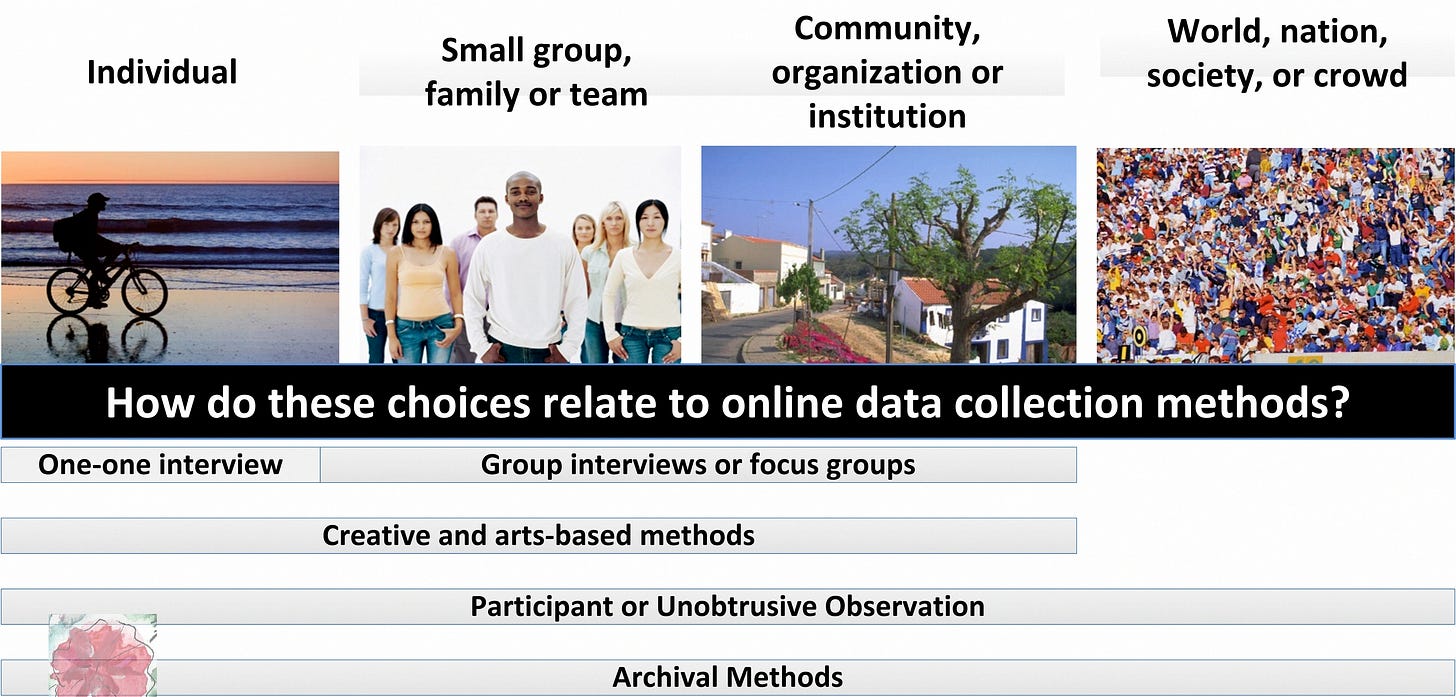

How can you match methods for data collection with the problem you want to investigate? One way is to think about the scope of the study and the unit of analysis. Are you looking at the problem from a big-picture or intimate vantage point? While there are no hard-and-fast rules, needless to say, the same methods won’t necessarily work in all situations.

World, Nation, Society or Crowd. At the broadest level are the researchers interested in global, societal, or cultural issues. They might be interested in systems, policies, changes, or events that touch many lives. They want to understand major trends and common or divergent experiences of the problem. They are interested in how problems manifest in different places or contexts. Topics might include political, social or environmental events or crises, poverty, epidemics, immigration, multinational business operations, economic developments, social movements or the environment.

Community, Organization or Institution. Other researchers are interested in one or more communities, organizations, institutions, agencies and/or businesses. While this kind of study might include large groups of people, they operate within some shared set of parameters. Researchers want to understand the systems, roles, policies, cultures, practices, or experiences of those who are more working, learning, or living together. Topics might include reform efforts, social responsibility, interorganizational relationships, management or leadership styles, or acceptance of change.

Group, Family or Team. On a smaller scale, when researchers study groups, teams or families they are exploring relationships, interpersonal dynamics, and interactions among people who know each other. Topics might include communication or collaboration styles or practices, conflict resolution, parenting or family issues.

Individuals. At the most fundamental level, qualitative researchers study attitudes, perceptions, or feelings of individuals. Topics could include any aspect of the lived experience.

For studies where the units of analysis are small-groups or individuals, the researcher might want data collection methods that include direct contact through interviews, or creative methods. Researchers studying groups might conduct group interviews or focus groups involving some or all members, depending on the size of the group. For larger scale studies, documents and records might help build an understanding of the issues.

In January I suggested this broad problem as an example: let’s say you are interested in defining a research problem concerning parenting issues with teenaged children. The nature of the study could vary depending on the scope of the study and the unit of analysis, as you can see:

World, Nation, Society or Crowd. What is the experience of parents of teenagers whose formative years occurred during the Covid 19 pandemic?

Community, Organization or Institution. What policies are needed to support parents who work at this organization?

Group, Family or Team. What are the roles of parents in multigenerational living arrangements?

Individuals. What is the experience of parents with teenage children?

Align Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) with Problems

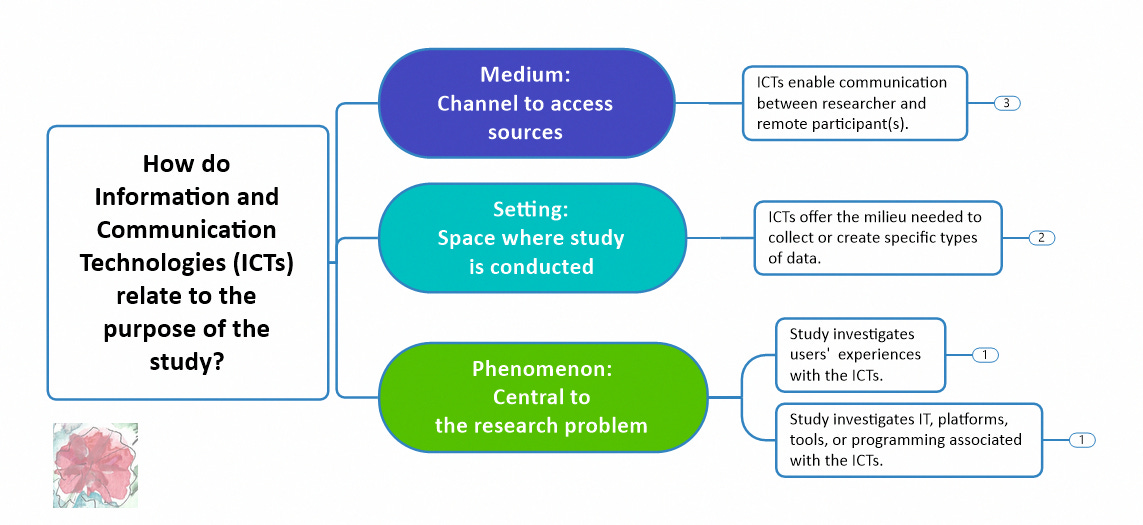

In the January newsletter I introduced this model as a way to think about the kinds of problems we might study: those that occur in the real-world, those that occur or are discussed and represented online, or problems associated use of the technology tool, app, or platform. Let’s look at this model again and explore the implications of each for data collection.

Is your goal to use an online communication medium to reach participants who are not in your geographic area, or those who would find it difficult to meet in a physical research setting? If so, then the kind of tool is less important than the access and comfort to the participant. One person might want to text, another to video chat, and that is fine.

Is your goal for using technology more specific? Do you want to be able to see the participant and observe nonverbal signals? If so your digital setting might be a video chat with those affordances. Or you might choose an online setting where the problem under investigation is represented or discussed. Do you want to learn how people use an app? If so, the specific ICT itself is the phenomenon you are studying.

Let’s revisit the problem concerning parenting issues with teenaged children.

Medium: You choose to do online interviews because you are conducting a global study and want to gain perspectives from parents in different parts of the world.

Setting: You choose to conduct a participant observation in an online community where parents discuss teenage children.

Phenomenon: You choose to conduct focus groups about how parents navigate an online portal for mental health services.

All of these are online studies, but the choice of ICT varies. In the first, it is simply a convenience. In the second, it is the space selected because it fits criteria set for the study. In the third, the researcher is interested in the usability and design of the online portal. A study might have more than one reason for using an ICT to collect data, but having a clear and specific sense of the purpose will mean the proposal is more understandable to reviewers.

Types of Data

Whether you are interacting with an individual or group of participants or collecting other kinds of source materials, qualitative data can take many forms. Some ICTs are focused on one type of data, while others offer a range of options or a mix of all types. In coming newsletters we’ll dig into ways to use different platforms and tools to collect various types of data with interviews and focus groups.

ICTs and Time-Response Options

Do you want participants to respond to prompts or questions immediately, or do you want to allow more time to think about a response? Do you want an ongoing, near-synchronous conversation so you can offer prompts at regular intervals? Do you want to allow more time for participants to collect examples, or complete some kind of activity, such as taking pictures or finding artifacts? These choices also play into the selection of ICT, and alignment with the problem you want to study and characteristics of the participants.

Keep learning!

This newsletter introduces a lot of considerations for selecting the methods to use and the technologies that can facilitate data collection. Yet there are still more decisions we’ll explore in future newsletters. For a deeper dive, consider a paid subscription to access additional materials or purchase Doing Qualitative Research Online. If purchasing from Sage, use this code UK25BOOKS, anywhere in the world.

ICYMI

This post builds on the January posts about choosing a problem to study:

Find questions: What problem merits and online qualitative study?

To find research questions: Ask those experiencing the problem and

Find open-access scholarly journals in the social sciences

If you are interested in purchasing my books from Sage, use this code for a 30% discount on ebooks: UK30BOOKS.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Thanks to Beth Spencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!

Very useful information. Many thanks for sharing.