Originality and Our Scholarly Voice

We can’t speak with our own voice using someone else’s words.

Our AcWriMo 2024 focus is on originality.

This month I’m offering weekly posts to celebrate Academic Writing Month.

Week 1 Define what originality means for you and use critical and creative thinking.

Week 2 Develop a scholarly voice and find the courage to speak.

Week 3 Communicate insights. Offer clear explanations. Create stories or examples.

Week 4 Encourage originality: Create a culture of inquiry in the classroom.

Speak with a scholarly voice.

We express our thoughts in an original way by speaking with our own unique scholarly voice. Adrian Holliday, author of Doing & Writing Qualitative Research, observes that academic writers have a particular dilemma: we must balance extensive reference to others' work with our inclusion of own perspectives. We need to demonstrate our knowledge of prior published literature about the topic at hand, while at the same time explaining our own interpretations and critical insights. Similarly, Ken Hyland observes that “academic writing… is an act of identity: it not only conveys disciplinary ‘content’ but also carries a representation of the writer” (Hyland, 2002, p. 1092). We represent something of ourselves – where we are coming from, what we value and respect, what we think is important enough to merit the time and effort it takes to conduct research and put our thoughts into words. Our words! We can’t speak with our own voice using someone else’s words.

We can’t ignore the fact that we are in a tech-pervasive time when it is all too easy to simply cut and paste others’ words. Now that we have generative AI tools, it is even simpler: just ask a robot to do the writing! Popular “mashup” culture blurs boundaries between acceptable and unacceptable use of others’ work. Let’s address a fundamental issue: if we represent work as our own that is not, we can’t make an authentic contribution to our fields. Anna Rogers offers another way to look at it: “claiming full credit for the result of your work is possible if and only if you know and cite your sources” which you can’t do when using an AI tool that offers no attribution to the sources, and no path for a reader to retrace your steps and locate the source.

For one of my first publications, “Expect Originality! Using Taxonomies to Structure Assignments that Support Original Work” (2008), I placed a options on a continuum to illustrate degrees of honesty and originality. I’ve updated it here:

On one side, we have intentional intellectual theft and misrepresentation that is obviously unethical plagiarism. In the middle of this continuum, we see the problems of ignorance or sloppy use of proper citations. These are issues that can be addressed by learning how to properly include quoted or paraphrased materials and work with the arcane particularities of APA, MLA, and other academic writing styles.

Also, on this side of the continuum we have the use of generative AI to write some or all of the paper. The National Association of Science Writers took a strong stand on the use of generative AI in this statement:

Accurate science news depends on, as it always has, people writing about science. New technologies emerge all the time, and now we have witnessed generative A.I. tools like ChatGPT and Bard that appear to have the ability to write with little human guidance. … [We at the National Association of Science Writers (NASW) commit to not using generative A.I. tools like ChatGPT or Bard to replace work done by human writers and editors. We also will not use A.I.-generated images, such as with DALL-E — except under very particular conditions and with artists directly involved, while ensuring the result neither imitates existing work nor infringes copyrights. … Ethical considerations and human agency must remain central to editorial decisions, as they always have been. For the integrity and accuracy of journalism [and scholarly publications], we must remain vigilant so that readers and writers alike can clearly distinguish between human- and algorithm-generated content.

I agree wholeheartedly that scientists, including social scientists, hold ourselves to a high ethical standard. The public is being bombarded with disinformation, misinformation, and pronouncements of instant experts who count “likes” as an indication of credibility. As academic writers we need to be trustworthy. Given this priority, each writer will need to reflect on ethical considerations in relation to tools they want to use. Is it acceptable to use AI tools trained on copyrighted material used without the consent of the writers or artists? Will the tool help us improve our writing or will it do the writing? Sage Journals makes a distinction between assistive and generative tools:

Assistive AI tools make suggestions, corrections, and improvements to content you’ve authored yourself…. Content that you've crafted on your own, but refined or improved with the help of this kind of Assistive AI tool is considered “AI-assisted”. The term Generative AI tools refers to tools such as ChatGPT or Dall-e which produce content, whether in the form of text, images, or translations. Even if you've made significant changes to the content afterwards, if an AI tool was the primary creator of the content, the content would be considered "AI-generated”.

We need to adhere to the policies and expectations of the journals and other potential publications about whether generative AI tools can be used, and if so, what kinds of tools, used in what way. We must be transparent about the use of such tools to avoid accusations of academic dishonesty or plagiarism. Very simply, if we represent work as our own that is not, we can’t make an authentic contribution to our fields and help make the world a better place.

Original writing in our own voice means developing the skills necessary to write in an academic style and to respect writers by citing them. It also means we need to take a step beyond proper forms of writing to make meaning from what we’ve learned from our own research and scholarly literature.

Becoming a Critical + Creative Scholar

The APA Publication Manual tells us:

The prime objective of scientific reporting is clear communication. You can achieve this by presenting ideas in an orderly manner and by expressing yourself smoothly and precisely. Establishing a tone that conveys the essential points of your study in an interesting manner will engage readers and communicate your ideas more effectively. … In describing your research, present the ideas and findings directly, but aim for an interesting and compelling style and a tone that reflects your involvement with the problem. (VandenBos, 2010, pp. 65-66)

How do we develop a tone and compelling style that is acceptable to editors, reviewers, or professors yet retains our original stamp? How do we represent ourselves while situating our work within the academic conversation of our respective fields? It takes courage to take a stand, make a claim, or call out a concern. We have to feel confident in our roles as scholars, as thinkers with something worthwhile to say. There are things we can do to cultivate our voices and build faith in our own abilities as scholars, so let’s get started!

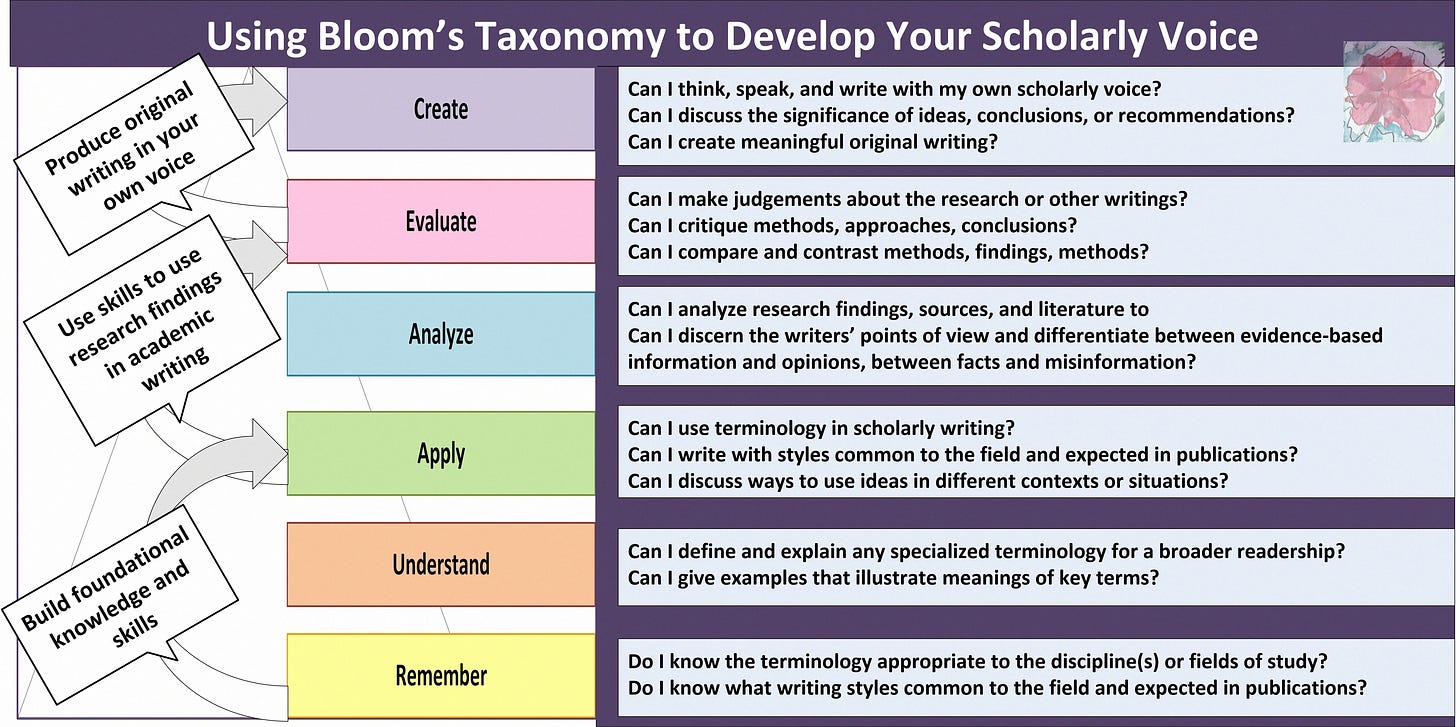

In the previous newsletter I built on Bloom’s Taxonomy as a way to consider how critical and creative thinking are inter-related in academic writing. Let’s take another look:

Original writing is predicated on learning how others write about the topic or problem. We first need to understand, and be able to explain, terminology and basic concepts. We build on these foundations when we analyze and evaluate the research literature. Lynn Nygard, author of Writing for Scholars, suggests that

[W]riting is a two-part process: the creative part, we would put our ideas into words, so they make sense to us; and the critical part, when we try to make those words make sense to someone else. In the creative part, we let the ideas flow, make new connections, see implications and draw conclusions…. In the critical part of the process, we emerge from our own little universe and shift our perspective to that of the reader. This is where we fill in the blanks, connect the dots, and generally put into words everything the reader needs to draw the same conclusion we draw, or to see the same connection we see. (p. 25)

Here are some questions we can reflect on to connect the dots and develop original insights:

How has the research problem or question changed over time?

What factors will influence the problem going forward? Are there trends or factors related to technology or demographic shifts, environmental, economic, social, cultural, or political issues, that will change how we need to define and study the problem?

How have the methods used to investigate the research problem changed? Why did previous researchers make the choices they did, and why would you do it differently now?

Were ethical dilemmas adequately addressed? Did you note ethical issues that were ignored?

Were cultural or indigenous peoples respected?

How does prior research on this problem compare and contrast in studies from diverse disciplines? From diverse cultures, settings, or perspectives?

What did researchers miss? What aspects of the problem have not been adequately studied? Whose perspectives are missing?

We build on these foundations when we analyze and evaluate what our own research process and findings:

What new questions emerged that we intend to study, or that we invite other scholars to explore?

What recommendations can we suggest for practice or policy making?

Could we have approached the problem in a different way, using other methodologies or methods? With a different population in another setting? Why? How?

We don’t want to stop there. We need to step out and say something more. Why should readers pay attention to what we have to say? Can we:

Tell a compelling story?

Express what we learned from the study in visual ways, with images, art, or visuals?

Describe our research experiences, share what we thought and felt about interacting with participants or discovering unexpected sources of data?

Explain the significance of our research? Why is it important for scholars, practitioners, parents, teachers, or the general public?

What does originality mean to you?

One way I shift from critical to creative thinking is to vary the actual ways that I write. I step away from the academically formatted page on the screen, go back to my notebook and sketch out my thoughts. Pen in hand, I can shape major concepts and look for new ways to connect or present them. Or, I might literally sketch a diagram or a mind map that helps me to see relationships in different ways. I often develop these sketches into figures that are included in my publications, because I think readers sometimes find the visual presentation more readily accessible than the written narrative.

In the last couple of years, I’ve discovered that voice-to-text software has greatly improved. I find that being about to speak can unlock the creative door. I can tell it, explain it, and then go back and carry out the critical part of the process to proofread and edit. Given the need to use citations and references, I’ve created a hybrid system of speaking and typing.

How have you put your own creative mark on academic writing? Look at a piece of your own writing, published or unpublished. What more could you say? How would you answer the questions listed above?

Use the comment area to share your thoughts or examples.

References

Anderson, L., Bloom, B. S., Krathwohl, D., & Airasian, P. (2000). Taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (2nd ed.). New York: Allyn & Bacon, Inc.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Book 1, Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay and Company.

Higgins, D. (2017). Finding and developing voice: enabling action through scholarly practice. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 14(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767333.2017.1282639

Holliday, A. (2016). Doing & writing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publication. See Holliday - Doing & Writing Qualitative Research - Chapter 6)

Hyland, K. (2002). Authority and invisibility: authorial identity in academic writing. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(8), 1091-1112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00035-8

Nygaard, L. P. (2015). Writing for scholars: A practical guide to making sense and being heard (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Salmons, J. E. (2007). Expect originality! Using taxonomies to structure assignments that support original work. In T. Roberts (Ed.), Student plagiarism in an online world: Problems and solutions. IGI Reference.

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (Sixth ed.). American Psychological Association.

Open Access Resources

Essential to Qualitative Research: The Human Component - 16 articles by Margaret Roller highlighting the human component associated w/ paradigm orientation, context & meaning, diversity & inclusion, nonverbal communication, giving sufficient time to derive useful outcomes https://t.ly/EmSSv

Finding Your Voice In Academic Writing (2021) by Deirdre McQuillan.

This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Business Researchers Portal at ARROW@TU Dublin.

Nonbinary Identities, Context, and Academic Writing by Cathy Mazak for the Sage Research Methods Community

what is an “original contribution”? by Pat Thomson

On Substack!

Meet my colleague Jenn Jenn McClearen, whose Publish Not Perish is a must-subscribe if you want to improve your academic writing! Check out these interesting posts:

Open Access Articles and Editorials

Allen, K.-A. (2024). A plea to journal editors: let people use their voice. Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 41(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1080/20590776.2023.2291147

Abstract. In academic writing, a writer’s unique voice can be lost in the pursuit of scholarly publishing. There is a specific tone and voice many academics have become accustomed to, but this voice is only sometimes representative of the diverse voices we would otherwise have the privilege to hear from if only they were not dissuaded from publishing or rejected at the Editor’s desk. The favouritism of one voice that reflects what a scholarly voice “should” sound like fails to acknowledge that all voices have something to offer.

Hyland, K. (2002). Authority and invisibility: Authorial identity in academic writing. Journal of Pragmatics, 34(8), 1091-1112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00035-8VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.) (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. (Open Access on Academia.edu)

Abstract. Academic writing is not just about conveying an ideational ‘content’, it is also about the representation of self. Recent research has suggested that academic prose is not completely impersonal, but that writers gain credibility by projecting an identity invested with individual authority, displaying confidence in their evaluations and commitment to their ideas. Perhaps the most visible manifestation of such an authorial identity is the use of first person pronouns and their corresponding determiners. But while the use of these forms are a powerful rhetorical strategy for emphasising a contribution, many second language writers feel uncomfortable using them because of their connotations of authority. In this paper I explore the notion of identity in L2 writing by examining the use of personal pronouns in 64 Hong Kong undergraduate theses, comparisons with a large corpus of research articles, and interviews with students and their supervisors. The study shows significant underuse of authorial reference by students and clear preferences for avoiding these forms in contexts which involved making arguments or claims. I conclude that the individualistic identity implied in the use of I may be problematic for many L2 writers.

Ismail, A., Ansell, G., & Barnard, H. (2020). Fitting in, Standing Out, and Doing Both: Supporting the Development of a Scholarly Voice. Journal of Management Education, 44(4), 473-489. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562920903419 (Open access on ResearchGate)

Abstract. What scholars call “writing” actually involves writing, reading, talking, thinking, and engaging. Yet how academic writing develops through this recursive, social process, is imperfectly understood. Although participating in academic gatherings like colloquia and international conferences can help researchers find a scholarly voice, not all new scholars have the opportunity to participate in such gatherings and the learnings they offer. Especially for those scholars, their academic writing must be consciously developed. We examine the process by which a new South African management scholar, supported by his writing coach, developed an academic voice. Analyzing their 15-month long communication (emails and summaries of conversations), we find three interweaving processes. Coaching guides the new scholar first to learn to fit in by becoming aware of genre conventions through practical writing-to-learn and show-and-tell coaching tactics. Then the challenge is to stand out by forcing tough trade-offs and intensifying the focus on novelty. Ultimately the scholar must do both, negotiating the tension between them. Our article provides evidence of how the emergence of self-reliant scholarly writing can be supported. This process is especially salient in developing country contexts with few enculturating opportunities, but we suggest that it applies more broadly, opening avenues for future theorizing.

Mitchell, K. M. (2017). Academic voice: On feminism, presence, and objectivity in writing. Nursing inquiry, 24(4), e12200. (Open access on ResearchGate)

Abstract. Academic voice is an oft-discussed, yet variably defined concept, and confusion exists over its meaning, evaluation, and interpretation. This paper will explore perspectives on academic voice and counterarguments to the positivist origins of objectivity in academic writing. While many epistemological and methodological perspectives exist, the feminist literature on voice is explored here as the contrary position. From the feminist perspective, voice is a socially constructed concept that cannot be separated from the experiences, emotions, and identity of the writer and, thus, constitutes a reflection of an author's way of knowing. A case study of how author presence can enhance meaning in text is included. Subjective experience is imperative to a practice involving human interaction. Nursing practice, our intimate involvement in patient's lives, and the nature of our research are not value free. A view is presented that a visible presence of an author in academic writing is relevant to the nursing discipline. The continued valuing of an objective, colorless academic voice has consequences for student writers and the faculty who teach them. Thus, a strategically used multivoiced writing style is warranted.

Cover image by mcmurryjulie from Pixabay. All other figures and images are original.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Thanks to @BethSpencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!