Originality and Academic Writing Month

This AcWriMo let's focus on originality. Discover your unique scholarly voice and make a contribution to your field of study.

Welcome to the November issue of When the Field is Online!

This is Academic Writing Month, known as AcWriMo. We won’t be looking specifically at online research since any kind of researcher needs to write about their work! To help you become confident developing and using your unique scholarly voice, this month you will receive four newsletters:

Week 1 Define what originality means for you and use critical and creative thinking.

Week 2 Develop a scholarly voice and find the courage to speak.

Week 3 Communicate insights. Create pictures, stories or examples.

Week 4 Encourage originality: Create a culture of inquiry in the classroom.

Paid subscribers will receive some additional perks. If you’d like more resources and chances to discuss research and writing while supporting my work as an independent scholar, consider a paid subscription. As an AcWriMo incentive I am offering a 30-minute consultation to the first 20 paid subscribers! I’ll review a draft or schedule a Zoom meeting to discuss your project.

First, one more resource about archival research!

If you read the October issue on Archival Methods for Online Researchers, you saw numerous links to resources housed in the U.S. Library of Congress. Would you like to learn about the resources available to researchers online and materials only available on-site? Are you curious about permissions or agreements required when using the sources you find? Do you want to know how Library of Congress staff can help you in your search ? I discussed these questions with Lara Szypszak, Reference Specialist in the Manuscript Division.

See the Library of Congress web archives here. Pose your question by clicking Ask a Librarian and get direct help from a member of the Library of Congress reference staff.

Academic Writing Month: A time to develop new skills – counting is optional!

We conduct research and write about it all year round, but in November we shine a spotlight on these efforts with AcWriMo. I use the term academic writing broadly to refer to writing that is based in empirical research – our own research or others’ research as reported in the literature. As academic writers, we hope the articles and textbooks we publish will advance thinking about a subject and motivate other researchers to carry unanswered questions forward. Our changing world calls for new thinking, not just another dry discussion of findings from research that doesn’t offer ways to make a difference. To create real impact, we need to find and engage curious readers who will delve into our work to discover and learn something more. We have the potential to reach readers by incorporating original insights into our writing. While it is essential to reference the scholars whose shoulders we stand upon, we can take a step further and add our own original contributions to the scholarly discussion.

On social media many commenters express AcWriMo writing goals in quantitative terms. They discuss progress in terms of the number of words they produce, and their relative proximity to the finish line for an article or dissertation. Reading these statements, I wonder: what about goals for harnessing the potentially transformative meaning of those words? What about goals for creating tangible benefits for readers, whether they are scholars, practitioners, or members of the general public? AcWriMo 2024 is a time to reflect on our identities as academic writers, and to articulate goals focused on the development of our craft, so we can move it to a higher level.

Set goals for developing new creative and critical thinking skills

Creative thinking, critical thinking, and originality are more than buzzwords. What do these terms mean, and how can we use them to better understand our roles as researchers and writers? Here are some basic definitions:

Merriam-Webster offers a simple and concise definition of critical thinking:

the act or practice of thinking critically (as by applying reason and questioning assumptions) in order to solve problems, evaluate information, discern biases, etc.

The American Psychological Association’s Dictionary of Psychology places critical thinking in a research context:

a form of directed, problem-focused thinking in which the individual tests ideas or possible solutions for errors or drawbacks. It is essential to such activities as examining the validity of a hypothesis or interpreting the meaning of research results.

The American Psychological Association’s Dictionary of Psychology offers these definitions:

Creativity is the ability to produce or develop original work, theories, techniques, or thoughts. A creative individual typically displays originality, imagination, and expressiveness. Creative thinking is the mental processes leading to a new invention, solution, or synthesis in any area. A creative solution may use preexisting elements (e.g., objects, ideas) but creates a new relationship between them. Products of creative thinking include, for example, new machines, social ideas, scientific theories, and artistic works.

The Collins English Dictionary says originality is:

the quality or condition of being original [not a copy], or the ability to create or innovate.

Critical and creative thinking are intertwined in the research process. D.F. Halpern, in the International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2001) described the interplay of creative and critical thinking:

Creative thinking is the production of unusual and good responses to problems…. By comparison, the thinking skills used in critical thinking could be either common or unusual. Thus, critical thinking is a superordinate of creative thinking. Critical thinking requires creativity (unusual and good solutions) in many aspects—generating alternatives to problems, redefining goals, and recognizing which critical thinking skills are needed in novel situations.

Critical thinking starts with a curious and open mind, and a willingness to look deeper and wider than did those who explored the question before. We aim to balance breadth and depth. We look deeply at sources to consider what problems were studied and whose perspectives were represented (or missed). We look widely to cross established boundaries of field, discipline, culture, and geography. We use creative thinking to take a fresh look at the problems, questions, and potential solutions.

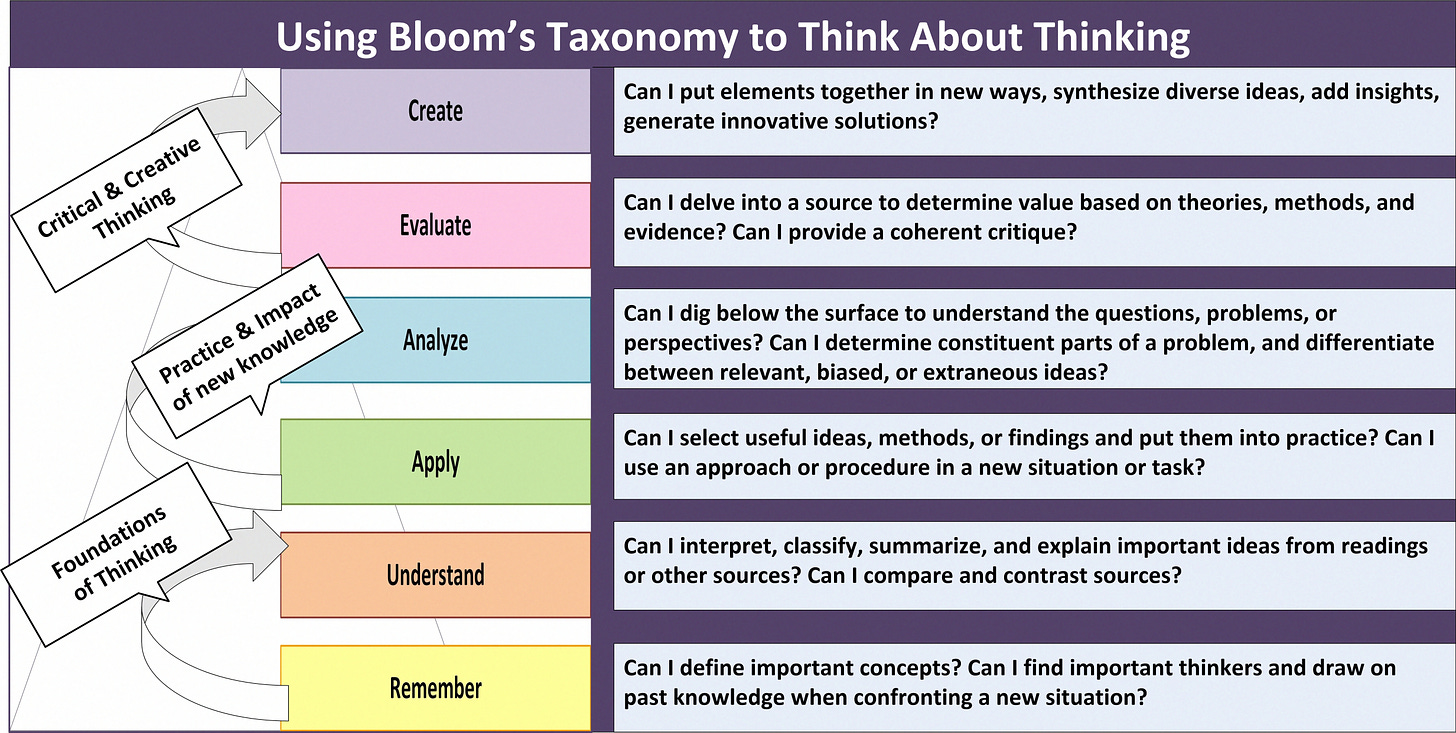

To connect these definitions and situate them in an academic writing context, I'll draw on and adapt the (updated) Bloom's Taxonomy (1956, 2000).

This taxonomy lays out dimensions of thinking involved with acquiring, using, and generating knowledge. With the categories of remember and understand we are reminded that whenever we approach an unfamiliar topic we need to focus on the foundations. We need to identify important epistemologies, concepts, methods, and seminal thinkers. We need to be able to do more than regurgitate what we’ve found; we need to be able to apply what we’ve learned in new situations. Thought processes associated with analysis and evaluation, central to the definitions for critical thinking, build towards the ability to create new ideas or solutions.

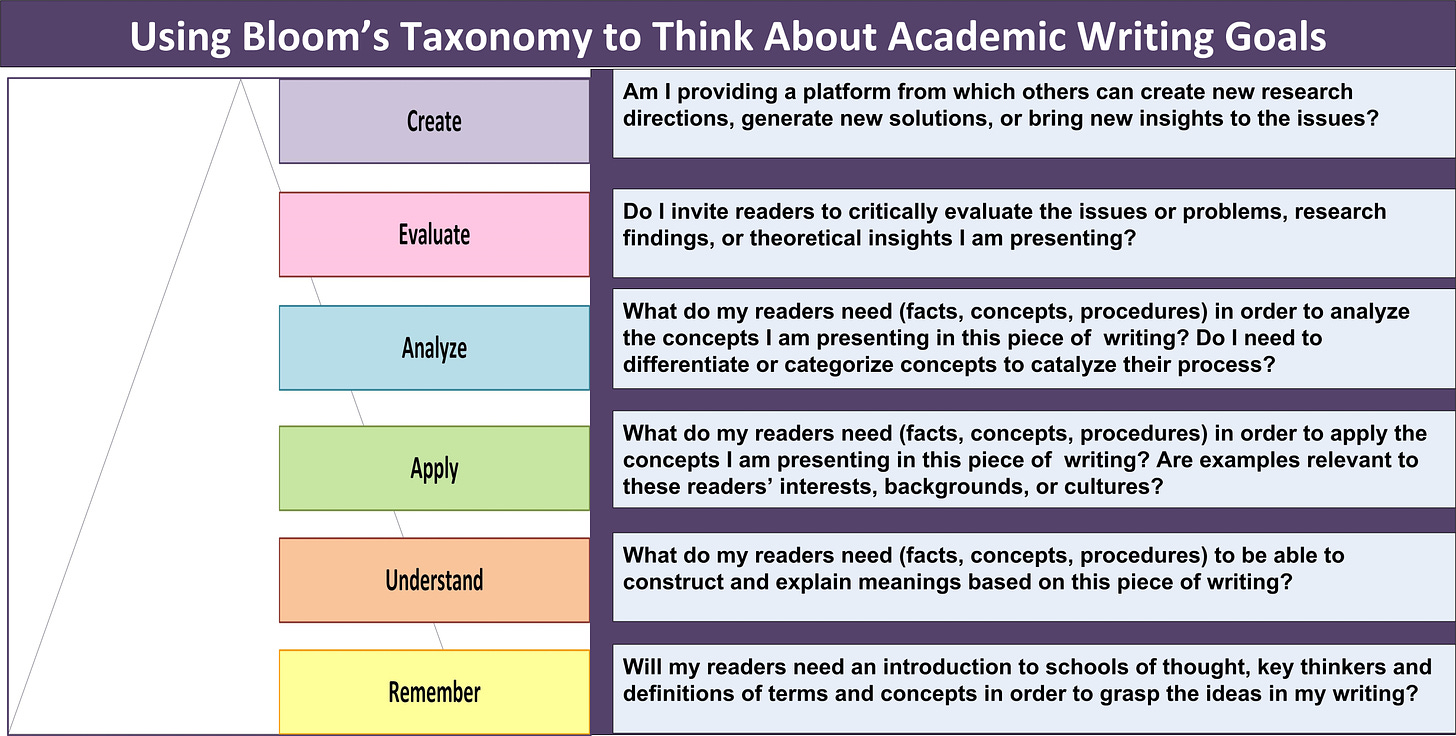

Here is another set of questions using Bloom’s Taxonomy to set writing goals:

While presented in a linear manner in these figures we don’t typically move through these ways of thinking in a sequential steps. As researchers and academic writers we need the ability to move across these dimensions, using both critical and creative thinking at various stages. We analyze problems, evaluate evidence, and generate answers, solutions, or new understandings. If we take the critical side, that is, the analysis and evaluation, without the creative side, we haven’t accomplished anything significant by conducting the research. When we include the creative side, that is, the ability to synthesize and innovate, the research can fulfill its purpose and make a difference.

We all have different strengths and natural tendencies - some of us prioritize the practical side of application while others love to immerse themselves in the foundational literature. Being creative, innovative, and original means we need all kinds of thinking.

Consider where you need to develop your critical and creative thinking skills

and set goals to work on this month.

Some writers might be concerned that by adding our own insights we sacrifice objectivity. Lynn Nygaard, in her excellent book Writing for Scholars, suggests that:

Objectivity refers primarily to the extent to which the scholar relies on external criteria, facts, or evidence in making a choice or reaching a conclusion. Subjectivity refers to the extent to which the scholar relies solely on personal thoughts and feelings. So, objectivity is not related to whether or not you have exercised judgement, but rather to what you have based that judgement on. … Your challenge as a writer is to demonstrate the objectivity of the choices and interpretations you’ve made, to reveal to the reader how you got from A to B. (p. 45)

In other words, we need to build on reliable foundations, adhere to scholarly and ethical principles, and be transparent when explaining how we derived interpretations and insights. This melding of critical and creative sides of the thinking process are essential if we want to accomplish the goal central to scholarly research: to make an original contribution.

Let’s get started! Reflect on key questions so the blank page isn’t so intimidating.

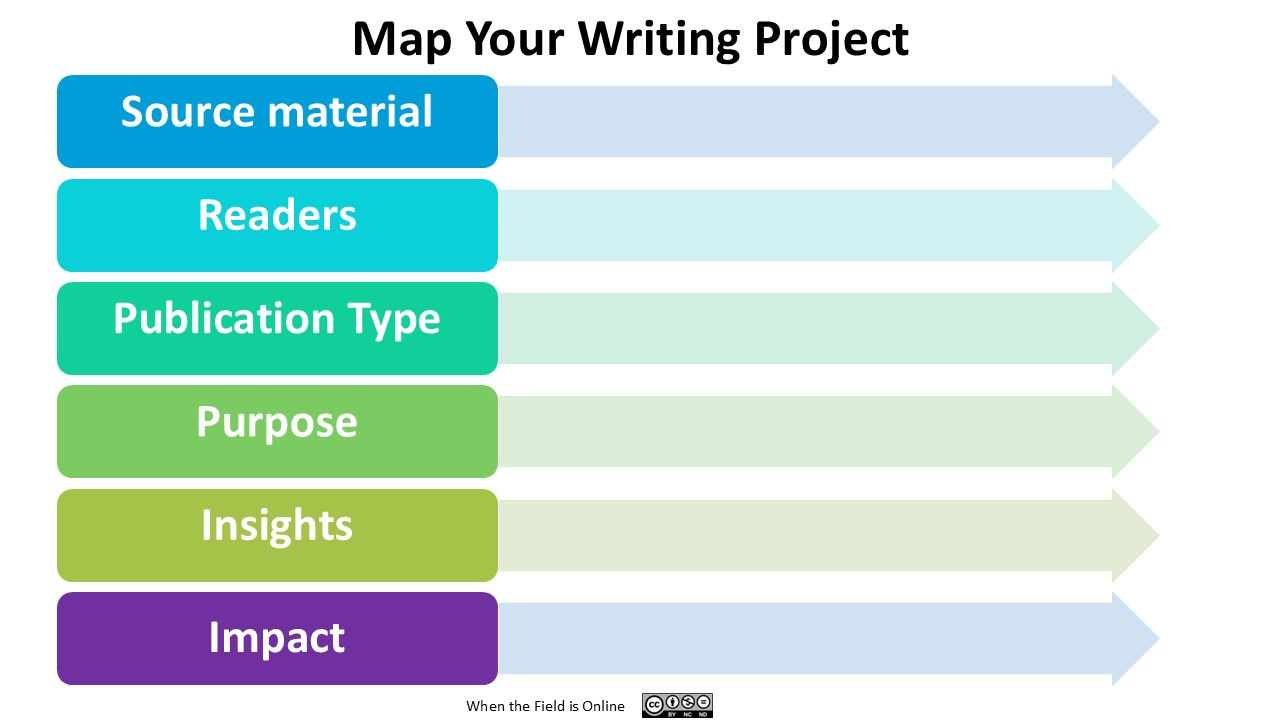

Where do we start? What will we write about, for whom, to achieve what purpose? While we may have a clear idea about the content, the focus and style of our writing vary depending on the readers we hope to reach. Will this target audience understand foundational principles and terminology, or do we need to explain the basics? Will they read a full-length article, or would they prefer to see a shorter one that is illustrated with diagrams or photographs? Do they want an in-depth discussion of the data collection and analysis, or stories that convey personal perspectives? Should we delve into scholarly intricacies or translate our findings into practical how-to steps? What purpose do we hope to achieve, what impact do we hope our work will have? Do we hope our work is scholarly, instructional, informative, or the basis for policy changes or new professional practices?

Thinking about your current project, how do you answer these key questions?

What kinds of source material will I draw on for this writing project? What foundations underpin the project? Is the research reliable? Is cited literature or other material up to date? Are the sources adequate? Do I need some additional background information or scholarly literature?

Who are the readers I want to reach? What parts of the source material will they want to learn about? What should I summarize or explain in depth? Does the audience already have an interest in your topic, or an I trying to introduce them to something new? Does my audience have background knowledge of key concepts and terminology?

What publication(s) will reach the target audience of readers? Where do my readers get trusted information?

What purpose will the publication serve? Am I concerned about advancing scholarship on this topic or helping readers to apply new ideas in practice? Am I trying to simply inform my audience about my research or findings, or do I want them to be prepared to take some kind of action? Do Iwant to provide evidence they can use to support planning or decision-making processes? Do I want readers to apply research findings? If so, I’ll target content accordingly to minimize the academic details such as your research design and methods and focus on the recommendations I uncovered.

What insights can I add? How can I use critical and creative thinking to make this project more valuable to readers? Do I have experiences to share? Can I use stories or examples to make important points? Are there judgements, recommendations or other explanations I can add to this piece of writing?

What impact will be possible? If I serve the purpose and reach these readers, what difference will this publication make?

The answers to these questions will shape the form, length, and approach you will take to filling in those blank pages.

Over to you!

What does originality mean in the context of your research and academic writing? Use the comment area to share your AcWriMo goals or current academic writing project. How will you develop the critical and creative skills needed to make an original contribution?

References

Anderson, L., Bloom, B. S., Krathwohl, D., & Airasian, P. (2000). Taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (2nd ed.). New York: Allyn & Bacon, Inc.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Book 1, Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay and Company.

Open Access Resources

The Link between Critical Reading, Thinking and Writing

Blog post by Alex Baratta, author of How to Read and Write Critically (2022) and Read Critically (2020).

Learning to be Original: In the Age of AI, Students Need to be Taught the Skills of Innovation

Blog post by Alastair Bonnett, author of How to be Original: Transform Your Assignments and Achieve Better Grades and How to Argue.

Nearly 100% of my reference images come from loc.gov. I look forward to listening a bit later!

Hi Janet, this is a great encouragement to look differently at AcWriMo, which - while a great initiative in theory - I think often adds considerable pressure for academic writers at a difficult time of year. Love the idea of taking this approach to it!

This AcWriMo I'm committed to publishing 30 tiny pieces of writing, to air out some ideas that have been in the margins of notebooks for way too long. I want to set them off into the wild, and see where I get to!