Encourage originality: Create a culture of inquiry in the classroom

Guide students to use critical and creative thinking in their research and writing.

Teaching and Learning Research Methods

This Academic Writing Month, AcWriMo, the focus is on originality with weekly posts. Here are the first three, in case you missed them:

Week 1 Define what originality means for you and use critical and creative thinking.

Week 2 Develop a scholarly voice and find the courage to speak.

Week 3 Communicate insights. Create pictures, stories or examples.

I’ve discussed a developmental process for infusing critical and creative thinking into our research, adapting Bloom’s Taxonomy as a framework. This week we’ll look at how to encourage others to aim for original thinking and writing. How can we create a learning environment that motivates learners to ask hard questions? How can we create active-learning opportunities that allow them to gain research skills needed to discover answers? How can we create opportunities for practical inquiry?

In this newsletter, find my introduction, an interview with fellow Substack newsletter editor Vicky Loras, and a curated collection of open-access articles, webinar registration and recordings, and more resources.

How can research activities build critical skills researchers, professionals, and citizens will need in the future?

The philosopher John Dewey wrote about education in an era with remarkable similarities to our own. When the telegraph and telephone opened immediate communication across the oceans and continents, Dewey observed that while these technologies had broken down barriers “to bring peoples and classes into closer and more perceptible connection with one another. It remains for the most part to secure the intellectual and emotional significance of this physical annihilation of space” (Dewey, 1916, p. p. 85). We are still grappling with the intellectual and emotional significance of a multicultural global society.

In Dewey’s time the nature of work was changing with the Industrial Revolution, and he saw a corresponding need to change the nature of education. He described the prevalent view of teaching and learning as largely passive: we’ll tell you what you need to know. Dewey characterized it this way: “the subject-matter of education consists of bodies of information and of skills that have been worked out in the past; therefore, the chief business of the school is to transmit them to the new generation” (Dewey, 1938, p. 17). He criticized this attitude toward education as hopelessly out of step with the need to prepare students for the newly connected world. Instead, he thought students needed opportunities to actively learn from experience through problem-solving and reflection.

1938, really? Seems like this could have been written today. So many years later we revisit similar themes. We still grapple with the need to meaningfully, respectfully, bridge distances even though we live in a connected world. Strikingly, today, some welcome globalism and others fear it. We still contend with the educational dilemma Dewey described because simply transmitting information and skills is inadequate preparation for the challenges today’s students will face in rapidly changing academic, professional, and civic life. Technology has made it easier to copy and paste or ask an app or artificial intelligence for an answer.

In our time it is ever more important to know how to dig below the surface, discern fact from opinion, use scientific approaches to understand problems, support conclusions with empirically-derived evidence, interpret and apply findings in creative ways. Perhaps we need to create a culture of inquiry and invite students to ask big questions and discover future-oriented insights and solutions.

What are inquiry models?

Inquiry models of teaching aim to stimulate students’ curiosity and build their skills in finding, analyzing, and using new information to answer questions and solve problems thereby shifting from trying to transfer knowledge, to building new knowledge. Instead of providing facts, we create an environment where students are encouraged to look for new ways of looking at an understanding problems, discern important and relevant concepts, and inductively develop coherent answers or approaches. As Joyce et al. (2009) explain:

Humans conceptualize all the time, comparing and contrasting objects, events, emotions – everything. To capitalize on this natural tendency, we raise the learning environment to give test the students to increase their effectiveness. Working in using concepts, and we hope that consciously develop your skills for doing so. (p. 86)

They suggest 3 guidelines for planning this kind of learning experience:

Focus: Concentrate on an area of inquiry, within a specific domain, that is feasible for students to master within the timeframe of the assignment.

Conceptual control: Organize information into concepts, and gain mastery by distinguishing between and categorizing concepts.

Converting conceptual understanding to skills: Learn to build and extend categories, manipulate concepts, and use them to develop solutions or answers to the original questions.

How can we use inquiry models to teach research methods?

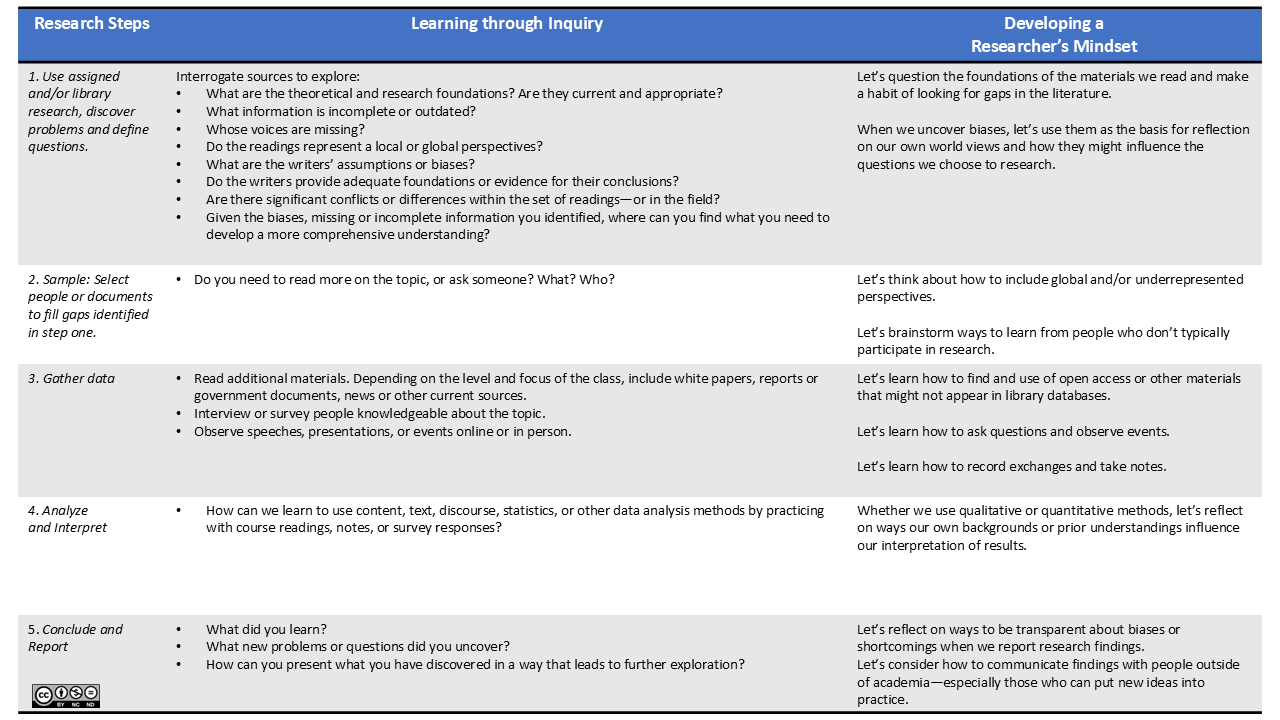

Online or face-to-face research activities, with related written reports, allow students to learn by doing. Here are a few ideas that could be used to apply inquiry-model guidelines with individual students or as team activities:

Focus: What Joyce et al. defined as focus aligns with the stages researchers describe as research design. Activities center on a deep dive into a specific domain. What are the unanswered questions in the materials we are reading or the topics we are discussing? What do we want to know, and what information is needed to answer what questions?

Approaches to gathering information could include online interviews with practitioners, experts, or individuals with experience in the topic at hand. Students can write about their observations of online activities, including posted videos, social media, online communities, and posted discussions. Or, ask students to find documents or visual records available online or in digital libraries or archives. (See this post about archival research online.)Conceptual Control: Conceptual control aligns with the stages researchers describe as data management and analysis. Once information has been collected, students organize, prioritize and explain relationships between key ideas. They move from single-attribute categories to more complex hierarchies of concepts.

Converting conceptual understanding to skills: This is the point where they can begin to develop habits of creative thinking. The above activities are of little use unless students can synthesize and make sense of what they’ve studied. What can they do with what they’ve learned? What skills were developed? What new questions will they need to answer next?

Joyce et al. suggest that learning activities organized in this way utilize inductive thinking, which “increases students’ abilities to form concepts efficiently and increases the range of perspectives from which they can view information” (p. 87). Surely students who have been actively engaged in these kinds of explorations will be better prepared to conduct empirical research.

Here are some additional thoughts for organizing active-learning activities. Depending on the available time and the nature of the class, you can use these ideas as the basis for team or individual projects and written assignments.

By moving from transmission to exploration, we can help students realize the importance of inquiry and value of their own ideas. They’ll learn how to communicate with people who are outside their own background or field of study. In the process, they will develop mindsets and skillsets that prepare them to be problem-solvers who are prepared to help us navigate the future in a complicated world.

References

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan Company. Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan Company.

Weil, M., Joyce, B., & Calhoun, E. (2009). Models of teaching (8th ed.). Boston Pearson. (Note: I’m referencing a 2009 copy, you can borrow a 2014 edition from the Internet Archive, or buy the new 2024 edition.)

What do new and aspiring PhDs need right now?

That is the question I posed to doctoral candidate Vicky Loras in this video interview. Learn more by subscribing to Meet the PhDs!

Open Access Resources

e-Prints from the National Centre for Research Methods, UK

Collins, Debbie (2024) Teaching Quantitative Social Science Research Methods Online. Manual. National Centre for Research Methods.

Lewthwaite, Sarah and Nind, Melanie (2021) Case Studies in Research Methods Pedagogy - Teaching ethnographic methods through facilitated discussion. Other. NCRM.

Nind, Melanie (2023) NCRM Bitesize Lessons for Teaching Social Science Research Methods 1: Active Learning. Manual. National Centre for Research Methods.

Nind, Melanie (2023) NCRM Bitesize Lessons for Teaching Social Science Research Methods 2: Experiential Learning. Manual. National Centre for Research Methods.

Nind, Melanie (2023) NCRM Bitesize Lessons for Teaching Social Science Research Methods 3: Learning from Learners. Manual. National Centre for Research Methods.

Open Access Journal Articles

Ghiso, M. P., Campano, G., Schwab, E. R., Asaah, D., & Rusoja, A. (2019). Mentoring in Research-Practice Partnerships: Toward Democratizing Expertise. AERA Open, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419879448

Abstract. Reconceiving relationships between universities, schools, and community organizations through research-practice partnerships, and building capacity for partnership work, necessarily entails rethinking the mentorship of graduate students. Our findings shift conceptions of mentorship from individual apprenticeship into a narrowly defined discipline to a collective undertaking that aims to democratize expertise and enact a new vision of the public scholar.

Mannion, N., Fitzgerald, J., & Tynan, F. (2024). Photovoice Reimagined: A Guide to Supporting the Participation of Students With Intellectual Disabilities in Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241270467

Abstract. Article 12 of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (1989) sets out the right for all children to be heard and for their opinions to be given due weight. However, the voices of children with disabilities often remain silenced as their perspectives are rarely consulted. This paper describes how a visual, participatory research method called Photovoice was used to elicit the voices of students with Intellectual Disabilities (ID) in mainstream post-primary schools in the Republic of Ireland.

Robinson, M. A. (2024). Qualitative Research As “A Voyage of Discovery”: An Interview with Ann Langley on Synergies Between Teaching and Publishing on Qualitative Methods. Journal of Management Education, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10525629241275036

Abstract. In this interview, Dr. Ann Langley draws on her extensive pedagogical and research experience to share insights on how she helps her students learn the fundamentals of qualitative research. These reflections provide inspiration and concrete examples of how, as Dr. Langley describes, both pedagogical considerations and “practical experience where I have encountered challenges” can morph into important theoretical and methods pieces, with the potential to push a field forward.

Rubenstein, L. D., Woodruff, K. A., Taylor, A. M., Olesen, J. B., Smaldino, P. J., & Rubenstein, E. M. (2024). “Important Enough to Show the World”: Using Authentic Research Opportunities and Micropublications to Build Students’ Science Identities. Journal of Advanced Academics, 35(3), 432-460. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X241238496

Abstract. Primarily undergraduate institutions (PUI) often struggle to provide authentic research opportunities that culminate in peer-reviewed publications due to “recipe-driven” lab courses and the comprehensive body of work necessary for traditional scientific publication. However, the advent of short-form, single-figure “micropublications” has created novel opportunities for early-career scientists to make and publish authentic scientific contributions on a scale and in a timespan compatible with their training periods.

Vang, M., Wolfgram, M., Smolarek, B., Lee, L., Moua, P., Thao, A., Xiong, O., Xiong, P. K., Xiong, Y., & Yang, L. (2023). Autoethnographic engagement in participatory action research: Bearing witness to developmental transformations for college student activists. Action Research, 21(1), 104-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/14767503221145347

Abstract. This article documents and analyzes autoethnographic engagement in participatory action research (PAR)—a reflective, irritative, and dialogic writing and team-discussion process which documents researcher-activist experiences and contextualizes them within the action research process. We document autoethnography as implemented in a research partnership between HMoob American college student activists and education researchers, to study the systems of oppression and inform advocacy to support HMoob American students at a predominantly white university. Autoethnography informs all aspects of the PAR project, from the development of research questions, to data collection, analysis, and writing, to the implementation of plans for action.

Xu, X. (2021). A Probe Into Chinese Doctoral Students’ Researcher Identity: A Volunteer-Employed Photography Study. Sage Open, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211032151

Abstract. Researcher identity has been widely studied as central to doctoral education. However, little is known about students’ emic conceptualization of what represents researcher identity based on their lived experience. Using a sample of 24 Chinese doctoral students in Australia, this study adopts volunteer-employed photography (VEP) to facilitate the participants’ delineation of their researcher identity.

How to Do Research and Get Published: A free webinar series from Sage Publishing

In my previous position at Sage Publishing I offered a series of webinars, including a collaboration with the wonderful Journals team. They offer this monthly series of very practical, interactive webinars. I was a presenter on a number of the webinars you can access from the archives. Take a look! You can also access a series of video interviews on this page: Meetings with Remarkable Researchers.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Thanks to Beth Spencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!

Image by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay