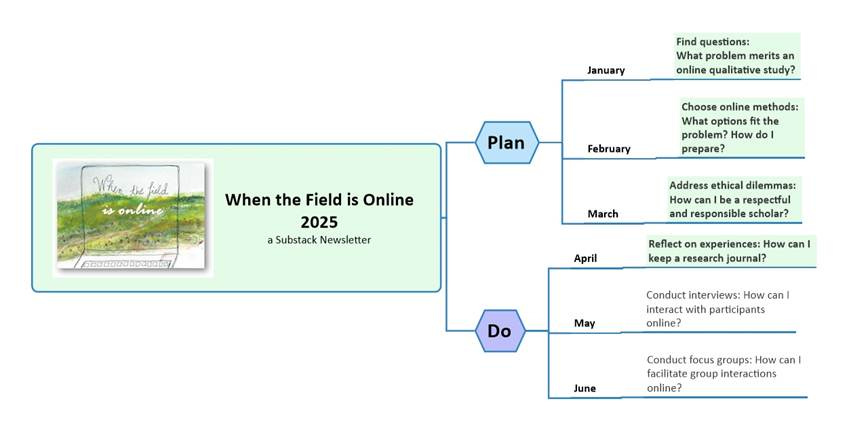

In the first half of 2025 we are working through important steps for any qualitative study, and in particular looking at steps involved in studies that use technology as a medium for collecting data from human participants.

In 2025 so far we have explored:

Find questions: What problem merits and online qualitative study?

To find research questions: Ask those experiencing the problem

In April we focus on reflexivity and journaling.

In this newsletter we’ll look at ways reflexivity is central to qualitative research; in another news blast later in the month we’ll play with ways to use reflexive journaling (analog and/or digital) for self-care. See part two of this series: Reflexivity in Practice.

What is reflexivity?

We can think about reflexivity in a research context and in a personal development context. When reflexivity is discussed in the context of research, definitions focus on reviewing the status of the study and being self-aware of biases, positionality, power, and influence. Here are two perspectives:

Reflexivity is a set of continuous, collaborative, and multifaceted practices through which researchers self-consciously critique, appraise, and evaluate how their subjectivity and context influence the research processes (Olmos-Vega et al., 2023, p. 241).

And

In the context of sensitive research, reflexivity has been defined as ‘a form of critical thinking which aims to articulate the contexts that shape the processes of doing research and subsequently the knowledge produced’ (Lazard & McAvoy, 2020, p. 160)

You can see that these definitions describe both group and individual activities. The ability to meld observation of ourselves and the world with introspection is central characteristics when reflexivity is discussed in a personal development context :

Reflexivity as a generative ability for internal deliberation (Archer, 2003).

‘Reflexivity’ is defined as the regular exercise of the mental ability … to consider themselves in relation to their (social) contexts and vice versa… Their reflexive ‘internal conversations’ are the means through which they deliberate about what course of action to take (Archer, 2010).

As qualitative researchers we are the research instrumentsbring our whole selves to our work, so we need to do all of the above. This is what I mean when I talk about left brain and right brain reflexivity: sometimes we need to be practical and analytical, and sometimes we need to be mindful and creative. Sometimes we are engaged with colleagues, students, or participants and other times we are navigating the depths of interior space.

Types of reflexivity

In 2003 Walsh articulated four inter-related dimensions of reflexivity. Olmos-Vega et al. (2018) identified key questions associated with each type to illustrate how we can look at research experiences through different lenses. (You might want to use these questions as journal prompts.)

Personal Reflexivity: Researchers reflect on their background, beliefs, experiences, motivations, and how these factors might shape their research decisions and interpretations. It also includes considering the impact of the research on the researchers themselves. Ask yourself: how are our unique perspectives influencing the research?

Interpersonal Reflexivity: This focuses on how relationships within the research team and between researchers and participants influence the study. Researchers should analyze power dynamics and their potential impact on data collection and interpretation. Ask yourself: what relationships exist and how are they influencing the research and the people involved? What power dynamics are at play?

Methodological Reflexivity: Researchers critically evaluate their methodological choices, ensuring these decisions align with their research paradigm and theoretical framework. They should be transparent about the rationale behind their methods and how they contribute to the study’s rigor. Ask yourself: how are we making methodological decisions and what are the implications?

Contextual Reflexivity: Researchers acknowledge how the cultural and historical context shapes the research questions, data collection, and interpretations. They should describe their relationship to the context and how it might inform their understanding of the data. Ask yourself: how are aspects of context influencing the research and people involved?

Archer, a sociologist and social theorist, came from a different angle: thinking about human agency (2003, 2010). She defined a typology of four modes of reflexivity: communicative, autonomous, meta and fractured. I’ve added some key questions:

Communicative reflexivity stems from internal conversations that require confirmation by others before resulting in specific courses of action. Ask yourself: what do I want or need to discuss with others? How might a collaborative approach be beneficial?

Autonomous reflexivity is defined as self-contained inner dialogues that lead directly to action without the need for validation by other individuals. Ask yourself: what do I prefer to keep private? How do I understand my own stage of life, work, place in the world?

Meta-reflexivity refers to the reflexive critique that subjects direct at their own internal conversations. Ask yourself: what larger, transcendent, existential questions am I wrestling with right now? How do my experiences and observations relate to my own beliefs, values, and ontological positions?

Fractured reflexivity is exercised by individuals whose inner dialogues do not allow them to deal properly with social circumstances. Ask yourself: how do I deal with a situation for which my education and experience have not prepared me? What am I struggling with, what cognitive dissonance or conflicting perspectives are challenging me?

These two sets of reflexivity types have some corresponding points: personal and autonomous, interpersonal and communicative. The others offer useful contrasts between considering the research approach and context and the introspective experience of contemplating ourselves as unique individuals in the world. In the next newsletter I`ll share examples and suggest some ways to integrate various types of reflexivity into your research practice and life discovery.

References

Archer, M. (2003). Structure, agency, and the internal conversation. Cambridge University.

Archer, M. S. (2010). Conversations about reflexivity. Routledge London.

Caetano, A. (2015). Defining personal reflexivity: A critical reading of Archer’s approach. European Journal of Social Theory, 18(1), 60-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431014549684

Olmos-Vega, F. M., E., S. R., Lara, V., & and Kahlke, R. (2023). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical Teacher, 45(3), 241-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

Walsh R. 2003. The methods of reflexivity. Humanist Psychol. 31(4):51–66.Watt D. 2007. On becoming a qualitative researcher: the value of reflexivity.

Learn more with these open-access articles!

Reflexivity

Arber A. Reflexivity: A challenge for the researcher as practitioner? Journal of Research in Nursing. 2006;11(2):147-157. doi:10.1177/1744987106056956 (Open access here.)

Abstract. In this article I focus on what it means to have a dual identity as a practitioner and a researcher within an ethnographic research study in the context of a hospice. I discuss moments when I experienced the tension between the roles of researcher and practitioner during fieldwork. I discuss some of the difficulties of managing the boundary between closeness and distance in terms of the observer and participant roles adopted. I explore the challenges for the researcher with a dual identity and how methods of reflexive accounting enhance the credibility of such a study. Thus I document the lived experience of my fieldwork; my thoughts and feelings when the insider and outsider identities collide; and how the identity crisis that resulted was resolved.

Burkitt, I. (2012). Emotional Reflexivity: Feeling, Emotion and Imagination in Reflexive Dialogues. Sociology, 46(3), 458-472.

Abstract. Theories of reflexivity have primarily been concerned with the way agents monitor their own actions using knowledge (Giddens) or deliberate on the social context to make choices through the internal conversation (Archer), yet none have placed emotion at the centre of reflexivity. While emotion is considered in theories of reflexivity it is generally held at bay, being seen as a possible barrier to clear reflexive thought. Here, I challenge this position and, drawing on the work of C.H. Cooley, argue that feeling and emotion are central to reflexive processes, colouring the perception of self, others and social world, thus influencing our responses in social interaction as well as the way we reflexively monitor action and deliberate on the choices we face. Emotional reflexivity is therefore not simply about the way emotions are reflexively monitored or ordered, but about how emotion informs reflexivity itself.

Caetano, A. (2014). Defining personal reflexivity: A critical reading of Archer’s approach. European Journal of Social Theory, 18(1), 60-75. (request here)

Abstract. Margaret Archer plays a leading role in the sociological analysis of the relation between structure and agency, and particularly in the study of reflexivity. The main aim of this article is to discuss her approach, focusing on the main contributions and limitations of Archer’s theory of reflexivity. It is argued that even though her research is a pioneering one, proposing an operationalization of the concept of reflexivity in view of its empirical implementation, it also minimizes crucial social factors and the dimensions necessary for a more complex and multi-dimensional study of the concept, such as social origins, family socialization, processes of internalization of exteriority, the role of other structure–agency mediation mechanisms and the persistence of social reproduction.

Enosh G, Ben-Ari A. Reflexivity: The Creation of Liminal Spaces—Researchers, Participants, and Research Encounters. Qualitative Health Research. 2015;26(4):578-584.

Abstract. Reflexivity is defined as the constant movement between being in the phenomenon and stepping outside of it. In this article, we specify three foci of reflexivity—the researcher, the participant, and the encounter—for exploring the interview process as a dialogic liminal space of mutual reflection between researcher and participant. Whereas researchers’ reflexivity has been discussed extensively in the professional discourse, participants’ reflexivity has not received adequate scholarly attention, nor has the promise inherent in reflective processes occurring within the encounter.

Karcher, K., McCuaig, J., & King-Hill, S. (2024). (Self-)Reflection / Reflexivity in Sensitive, Qualitative Research: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1–15.

Abstract. This scoping review offers insight into researcher well-being when working with sensitive and traumatic topics in a qualitative research context. The study identified existing empirical research concerning researcher well-being and mental health. The databases included SSCI, ASSIA < IBISS, Scopus, Social Policy and Practice, PsycInfo, Social Science Database/Social Science Premium Collection (Proquest), and Open Grey. An international search was conducted, with no time constraints on publication dates to gather as wide a selection as possible. 55 papers met the criteria. We found that the terminology used within the papers was not consistent which necessitated grouping the (self-) reflection/reflexive practices researchers used and categorizing them under the umbrella term SRR practices. The research questions were: 1. Which disciplines or fields are conducting SRR practices on sensitive topics? 2. What SRR practices do researchers employ in the context of sensitive research? 3. What were the self-reported outcomes from using SRR practices as a tool of researchers working on sensitive research?

Malacrida C. Reflexive Journaling on Emotional Research Topics: Ethical Issues for Team Researchers. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(10):1329-1339.

Abstract. Traditional epistemological concerns in qualitative research focus on the effects of researchers' values and emotions on choices of research topics, power relations with research participants, and the influence of researcher standpoints on data collection and analysis. However, the research process also affects the researchers' values, emotions, and standpoints. Drawing on reflexive journal entries of assistant researchers involved in emotionally demanding team research, this article explores issues of emotional fallout for research team members, the implications of hierarchical power imbalances on research teams, and the importance of providing ethical opportunities for reflexive writing about the challenges of doing emotional research. Such reflexive approaches ensure the emotional safety of research team members and foster opportunities for emancipatory consciousness among research team members.

Olmos-Vega, F. M., Stalmeijer, R. E., Varpio, L., & Kahlke, R. (2022). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical Teacher, 45(3), 241–251.

Abstract. Qualitative research relies on nuanced judgements that require researcher reflexivity, yet reflexivity is often addressed superficially or overlooked completely during the research process. In this AMEE Guide, we define reflexivity as a set of continuous, collaborative, and multifaceted practices through which researchers self-consciously critique, appraise, and evaluate how their subjectivity and context influence the research processes. We frame reflexivity as a way to embrace and value researchers’ subjectivity. We also describe the purposes that reflexivity can have depending on different paradigmatic choices. We then address how researchers can account for the significance of the intertwined personal, interpersonal, methodological, and contextual factors that bring research into being and offer specific strategies for communicating reflexivity in research dissemination. With the growth of qualitative research in health professions education, it is essential that qualitative researchers carefully consider their paradigmatic stance and use reflexive practices to align their decisions at all stages of their research. We hope this Guide will illuminate such a path, demonstrating how reflexivity can be used to develop and communicate rigorous qualitative research.

Subramani, S. (2019). Practising reflexivity: Ethics, methodology and theory construction. Methodological Innovations, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2059799119863276

Abstract. Reflexivity as a concept and practice is widely recognized and acknowledged in qualitative social science research. In this article, through an account of the ‘reflexive moments’ I encountered during my doctoral research, which employed critical theory perspective and constructivist grounded theory methodology, I elaborate how ethics, methodology and theory construction are intertwined. Further, I dwell on the significance of reflexivity, particularly in qualitative research analysing bioethics concepts. Through an account of the universal ethical principles that ‘I’, as a researcher, encounter, and a micro-analysis of the observed relationships that influence the theoretical construction and arguments developed, I explore the quandaries an ethics researcher undertaking a reflexive approach faces. I elucidate that reflexivity unveils – for both researcher and reader – how the researcher(s) arrive(s) at certain positions during the knowledge construction process. I conclude by stating that reflexivity demystifies the moral and epistemological stances of both the study and researcher(s).

Reflexive conversations

Caetano, A. (2017). Reflexive Dialogues: Interaction and Writing as External Components of Personal Reflexivity. Sociological Research Online, 22(4), 66-86. (sorry, this one is not open access!)

Abstract. Margaret Archer’s work suggests that reflexivity is exercised through internal dialogues, in which subjects talk to themselves in order to clarify ideas, mull over problems, make plans, and take decisions. The present article argues that the exercise of reflexive competences is not limited to the privacy of individual minds, but that there is also an external component, which can lend the concept a broader analytical scope. Using the results of qualitative research focused on the social mechanisms of personal reflexivity, including biographical interviews, the article examines two other modalities of exercising reflexivity: external conversations in interaction contexts and writing practices (autobiographical, creative, communicational, and organisational). It also looks at the differential activation of reflexivity according to both the subjects’ different positions in social space and inter- and intra-contextual variations.

Roddy, E., & Dewar, B. (2016). A reflective account on becoming reflexive: the 7 Cs of caring conversations as a framework for reflexive questioning. International Practice Development Journal, 6(1).

Abstract. Context: Some uncertainty surrounds both the definition and the application of reflexivity in participatory research and practice development. There is scope for further exploration of what reflexivity might look like in practice, and how the researcher/practice developer and participants might be involved. This paper does this in the context of a study that is using appreciative inquiry to explore the experience of inspection in care homes. Aims: I will explore my personal journey into the use of a relational constructionist approach to reflexivity and suggest that the 7 Cs of caring conversations provide a useful framework to inform reflexive practice. The 7 Cs will be used as a framework for the telling of this story.

Ross, K., & Li, P. (2025). Beyond Reflexivity: Centering Recognition and Relational Dialogue in Social Inquiry. Cultural Studies/Critical Methodologies, 25(2), 133–143. Abstract. In this manuscript, we develop the concept of recognition as a methodological concept, with a particular focus on its inter-subjective dimensions. Departing from the way recognition is used in much contemporary social theory and socio-political discourse, we suggest that recognition is a foundational methodological concept, related to but transcending methodological discussions of reflexivity, and with implications for meaning and validity. We ground our discussion in empirical examples that help illustrate the principles of recognition (and of misrecognition), and how researchers can attend to these principles in their own work.

Creative reflexivity

Chawla-Duggan, R., Konantambigi, R., Lam, M. M. S., & Sollied, S. (2020). A visual methods approach for researching children’s perspectives: capturing the dialectic and visual reflexivity in a cross-national study of father-child interactions. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2019.1672283

Abstract. The paper presents a visual methods approach from a cross national methodological project that used digital visual technologies to examine young children's perspectives in father-child interactions. The approach combines capturing the dialectic with visual reflexivity. The notion of 'capturing the dialectic' specifically by analysing conflict to gather the child's intention as their perspective, is underpinned by finding the contradictions in a situation of which children are a part. Visual technologies and in particular digital film does this, because it can identify difference, as it observes and captures the dialectic process.

Mansfield, C., Séraphin, H., Wassler, P., & Potočnik Topler, J. (2025). Travel Writing as a Tool for Sustainable Initiatives: Proposing a Dialogue Journaling Process Model. Journal of Travel Research, 64(2), 485–493.

Abstract. This study explores the transformative potential of travel writing, positioning it as a sustainable, dynamic, and adaptable tool crafted through written dialogue. It shows how travel stories, social media, new tech, and digital platforms work together and how they provide valuable data for research and potentially aid sustainability in tourism through a novel method. Introducing a Dialogue Journaling Process Model, we demonstrate the capacity of travel writing to raise awareness about sustainable practices, analyze the environment, and champion pro-environmental initiatives. Drawing from our pilot study in Slovenia, the findings provide a formal platform for dialogue and refinement. In advocating for the pivotal role of travel writing in advancing sustainable tourism, this research presents a method for this proposition.

Margolin, I., & Jones, A. (2023). Nine Women: Collages of Spirit-Collages of Self. Qualitative Inquiry, 30(2), 191-203.

Abstract. Collaging invites the twists and turns of meaning-making and insight. This Reflexive Inquiry illuminates the collages of nine artist women and celebrates the potency of harnessing Creative Consciousness through meditation, collaging, and dialogue. We aim for balance between juxtaposing evocative imagery, poetic rendering, responding with creative critical social justice understanding, and humility in this undertaking to evoke feeling and insight. The metaphor of the canoe crossing the river illustrates this journey. The fiercely powerful women in this inquiry were provided a pathway to heal from internalized injustices, empower themselves to take positive action, and discover a harmonized state from within.

Reflexivity in the Classroom

Berezan, O., Krishen, A. S., & Garcera, S. (2022). Back to the Basics: Handwritten Journaling, Student Engagement, and Bloom’s Learning Outcomes. Journal of Marketing Education, 45(1), 5-17.

Abstract. Often considered an enhancement to the learning experience, technology can also stifle creativity and higher levels of thinking. This study repositions students away from technology and back to the basics to stimulate engagement and higher levels of learning. It investigates the relationship between learning outcomes and the reflective journaling process in the context of an undergraduate marketing class in the United States. In addition, this study investigates a technique in which students are introduced to topics that are sensitive in nature, yet relevant to the real world. Although reflective journaling has been utilized in courses in areas such as educational psychology and social work, it has not been widely practiced in business courses such as marketing. Through the lens of Bloom’s Taxonomy, we qualitatively analyze handwritten reflective journaling assignments about loneliness and social media to determine how the process highlights higher levels of learning. The opportunity to use handwritten journals provided a unique learning experience and a hands-on approach to allow marketing students to experience learning in a new light.

Hibbert, P. (2012). Approaching Reflexivity Through Reflection: Issues for Critical Management Education. Journal of Management Education, 37(6), 803-827.

Abstract. This conceptual article seeks to develop insights for teaching reflexivity in undergraduate management classes through developing processes of critical reflection. Theoretical inferences to support this aim are developed and organized in relation to four principles. They are as follows: first, preparing and making space for reflection in the particular class context; second, stimulating and enabling critical thinking through dialogue, in particular in relation to diversity and power issues; third, unsettling comfortable viewpoints through the critical reappraisal of established concepts and texts; and fourth, supporting the development of different, critical perspectives through ideological explorations and engagement with sociological imagination. The article provides an elaboration of these principles and the issues associated with them as resources for critical management educators seeking to help their students develop their reflexive abilities. In addition, the article develops theoretically informed lines of inquiry for empirical research to investigate the proposed approach, which could help to further develop and refine theory and educational practice.

This license enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.

Thanks to Beth Spencer for this badge, indicating that no AI tools were used to create this post!